A double dose of Elliott Gould, steamy Nicholson, criminal Caan and an Albert Brooks classic all land in March 1981

Plus the first full-fledged flop of the year arrives

The premise is simple, but the task is not. Every single movie released in the United States during the 1980s, reviewed in chronological order, published month by month.

Buckle up, because this is The Last ‘80s Newsletter You’ll Ever Need…

MARCH

Blondie’s “Rapture” took the number 1 spot from Dolly Parton’s “9 to 5.”

Anchorman Walter Cronkite said goodbye to America.

RCA launched their much-hyped RCA SelectaVision VideoDisc system with titles like Casablanca, Heaven Can Wait, and Saturday Night Fever.

Ronald Reagan started to settle into his role as President, meeting with Margaret Thatcher and Pierre Trudeau, even as his new Secretary of State Alexander Haig accused the Soviet Union of promoting terrorism in Central America.

Then on March 30, the day before the Oscars, Reagan was shot in the chest by John Hinkley outside the Washington Hilton Hotel.

Remember the days when Bill Cosby was the safest thing at the movie theater?

Every time spring break rolled around, we would go to Memphis. That’s where both of my grandmothers lived, and typically at least one of my parents would also go with me. This was the last year before I started going on my own, and it was the last year I was interested in seeing family-friendly movies. It’s weird, though, because I was also itching to see grown-up movies at the same time, and I was largely losing the fights I was choosing.

When I say fights, let me paint the picture for you. I would read about a movie or see Siskel & Ebert talk about it or someone’s older brother would talk about something they saw and I would decide that my life would end if I did not somehow immediately see the film. I would begin a campaign with my parents and, depending on the time of the year, the title, and the degree of difficulty, I would also start the campaign with my grandparents, my friends’ older brothers… anyone who could get me into that theater by whatever means necessary. Campaigning took place in stages. First, I’d just casually mention reviews or articles I’d read, and let me tell you, working Bob Rafelson’s Postman Always Rings Twice remake into casual conversation as a ten-year-old is tricker than you’d think. Then I’d start mentioning how much I’m sure they would like to see the thing, as if I wasn’t even part of the equation. Then finally I’d make my pitch, saying that since they were probably going to go, they might as well take me along, too. It could take days for me to go through all the steps, fooling absolutely no one in the process.

I had to be careful when I was constructing my arguments. Citing Time magazine got me a lot further in a conversation with my parents than citing a source like Fangoria, which was responsible for a lot of my frustration at the time. I had to frame things so they seemed like my life would be enriched in some way by seeing them, and horror films were easily the hardest thing to make the case for with my parents. There was no way I was going to talk them into The Final Conflict because they both saw the original Omen in theaters, and with every poster for The Funhouse promising that it was from the director of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, that was another non-starter. There were films I was curious about but afraid of, too, like Bill Lustig’s Maniac. The Fangoria layout for that film freaked me out so completely that it took me decades to work up the nerve to actually watch the movie. When I worked at Dave’s Video, an industry-heavy laserdisc store in the Valley, Lustig was one of our regular customers, and I got to know him over several years. I eventually told him how scared I’d been of his movie and how powerful those images of the Tom Savini make-up were. He seemed delighted, and talking to him about the entire history of exploitation films, he was clearly proud of his film’s place in the margins of horror history.

It must have also been very strange for my parents because of the range of things I asked to see. I was at a strange age, still interested in Disney fare like The Devil and Max Devlin, but absolutely frantic to see things like Excalibur. I wouldn’t know what to make of me, either, to be honest, and I give my parents credit for putting up with my weird obsessions. My grandmothers went further than that, indulging me fully, and my grandmother Ruby would go so far as to send me the newspapers from Memphis the week before I came to see her so I could see all the ads for what would be playing when we were in town. It was not the best line-up this particular year, though, and I ended up seeing Devlin and the equally risible On The Right Track. This month would have been a complete bust for me if not for my dad, who took me with him for a long day of errands and chores and tasks that was capped off with a trip to the theater. He picked the movie he thought looked most interesting, and as a result, Thief landed on me like a ton of bricks. I had no idea what to make of the movie’s attitude or style, but I loved seeing it on a giant screen, and it stuck with me.

Overall, this is a month of misfires and messes, and we’re going to set that tone in a big way with our first film, the textbook definition of a garbage fire…

MARCH 6

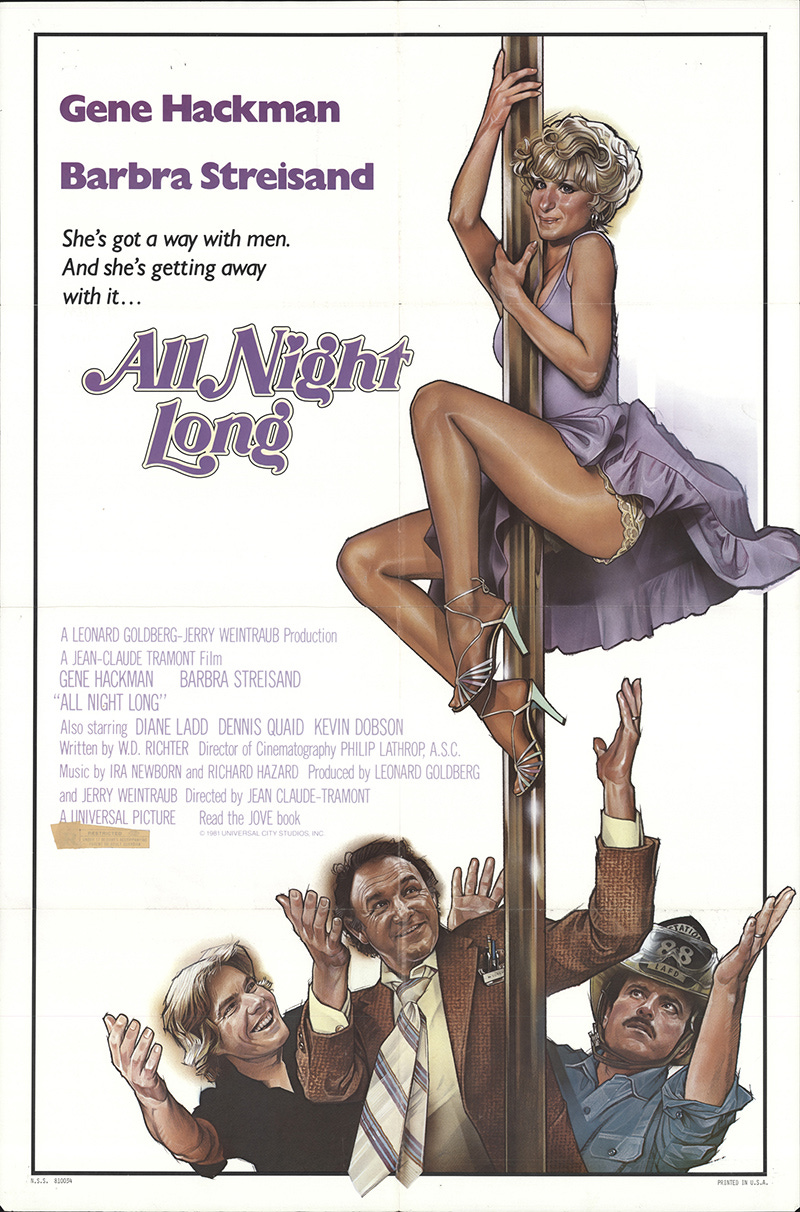

All Night Long

Gene Hackman, Barbra Streisand, Diane Ladd, Dennis Quaid, Kevin Dobson, William Daniels, Ann Doran, James Nolan, Judy Kerr, Marlyn Gates, Raleigh Bond, Mitzi Hoag, Charles Siebert, James Ingersoll, Tandy Cronyn, Len Lawson, Terry Kiser, Vernee Watson, Chris Mulkey, Steven Peterman, Richard Stahl, Faith Minton, Jessie Lawrence Ferguson, Nicholas Mele, Joe Jacobs, Demetre Phillips, Lomax Study, Annie Girardot, Bonnie Bartlett, Eunice Christopher, Virginia Kiser, Irene Tedrow, Peggy Pope, Marilyn Tokuda, Hamilton Camp, Gary Allen, Charles White-Eagle, Adrienne Leonetti, Dominico Sunzeri, John Dyar, Burc Lander, Robin Reed, Holly Addy, Paul Valentine, Timothy O’Hagan, Tom Regan, Kendall McCarthy, Gary Reynolds, Robert Mitchell

cinematography by Philip H. Lathrop

music by Ira Newborn

screenplay by W.D. Richter

produced by Leonard Goldberg and Jerry Weintraub

directed by Jean-Claude Tramont

Rated R

1 hr 27 mins

A man is demoted and ends up managing an all-night grocery store while also juggling an extra-marital affair with his own son’s married girlfriend.

Jean-Claude Tramont was a working writer with a few credits under his belt like Ash Wednesday (a weird Liz Taylor melodrama) and the French film Focal Point, which he also directed, but it was his marriage to one of Hollywood’s biggest power agents of the ‘70s, Sue Mengers, that gave him his biggest access to the industry. Mengers got him set up at Fox with a development deal for an idea he had about people working the night shift in Los Angeles and falling in love. He hired W.D. Richter to write the film and even when Fox put it in turnaround, Tramont was convinced he had gold on his hands. Mengers used her muscle to get Universal to pick it up with TV producers Jerry Weintraub and Leonard Goldberg attached.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Last '80s Newsletter (You'll Ever Need) to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.