Cronenberg's blowing up heads and Lily Tomlin's getting small in January 1981

Plus a proto-POLICE ACADEMY and the weirdest film I've reviewed yet

The premise is simple, but the task is not. Every single movie released in the United States during the 1980s, reviewed in chronological order, published month by month.

Buckle up, because this is The Last ‘80s Newsletter You’ll Ever Need…

JANUARY

The US minimum wage was raised to $3.35 per hour.

A deal was closed to release 8 million dollars in frozen assets in order to secure the release of the 52 US Embassy workers being held hostage in Iran, and they were returned home on January 25th.

Hill Street Blues made its debut on NBC.

And finally, Elijah Wood was born the same day that President Reagan signed an executive order that ended all federal price and allocation control on gas and fuel oil.

I’m pretty sure I saw exactly one of these movies released in January of 1981 in a theater.

January is no longer the wasteland it used to be. At this point, studios have turned pretty much every single spot on the release calendar into a battleground, and the right marketing seems to be able to turn any weekend into a potential blockbuster weekend. That was not always the case, and all you have to do is run through this month’s full line-up to see just how bad it could get.

As we go through this project, there are several different types of reviews I’m writing. There are films that I saw in the ‘80s that I remember well and have revisited repeatedly. There are films I did not see in the ‘80s, but that I was familiar with for one reason or another. There are films I am genuinely discovering for the first time, and there are movies that I saw and don’t remember and it almost feels like they’re brand-new.

One of the most common occurrences is embodied in one of this month’s titles. There are two different films, both released during the ‘80s, with nearly identical titles, and I have had the two of them merged into one vague thing in my mind for decades. I finally watched My American Uncle for this month’s newsletter, and I’ve always thought this was a drama about a Canadian girl and her much-older relative who comes to visit. Turns out, that’s My American Cousin, and we won’t get to that one for a few years. There are so many films that got tangled up in my memory because of similar titles or similar posters or some other coincidental connection.

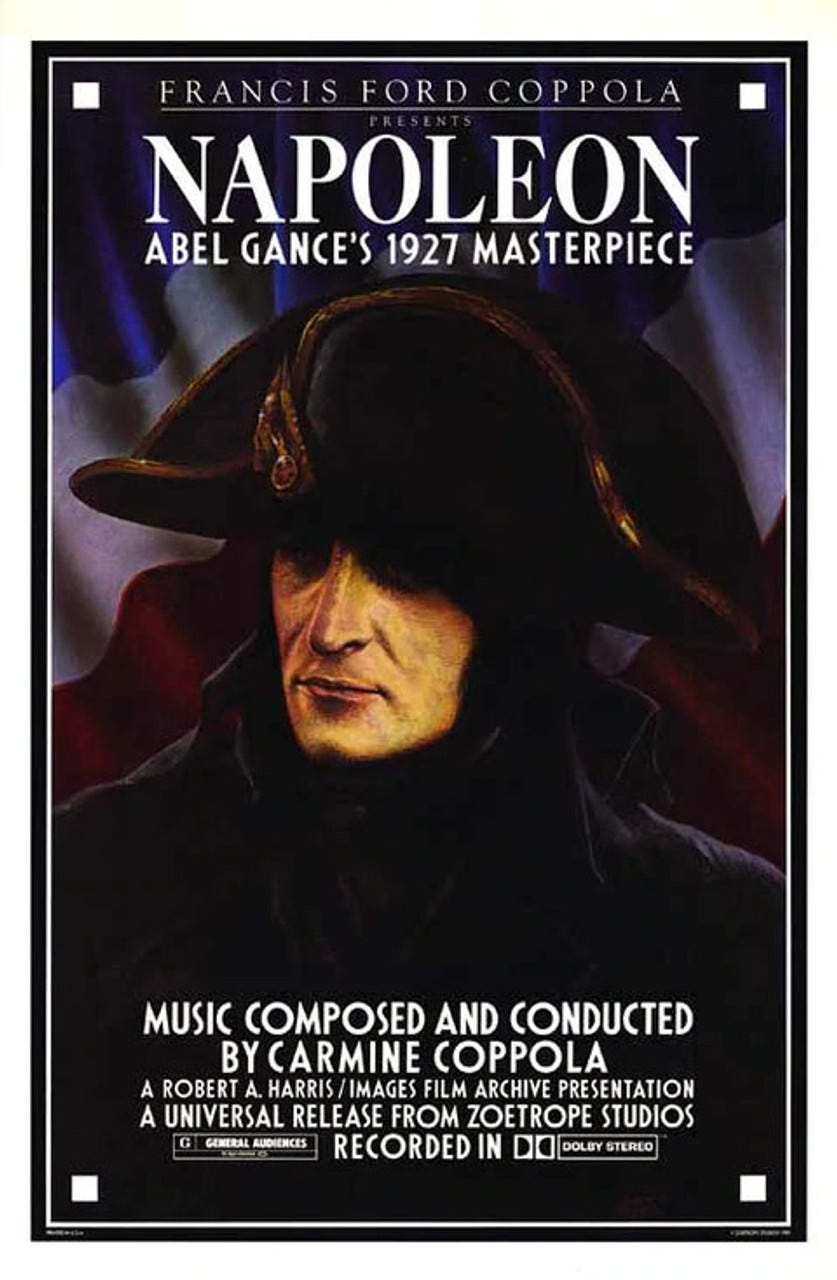

There was a title this month I would have desperately wanted to see in the theater, but at ten, there was no way I could have gotten to New York for the Radio City Music Hall presentation of the restored silent epic Napoleon. They were sold-out events, and they used the original three-screen process that director Abel Gance designed to showcase the climax of his movie. I’ve never seen it presented that way, but I did see the movie on the big screen in 2007, which may have been the last time it screened in Los Angeles. I read everything I could find about it in 1981, fascinated by the notion of this five-hour movie being presented in this very experimental way. Roger Ebert wrote of the 1981 experience, “The presentation of Abel Gance’s Napoleon is one of the great entertainment events of the 1980s, and the logistics of the event are little short of miraculous,” and I spent much of January and February seething that I wouldn’t get to see it even though, at age ten, I had barely seen any silent films at all.

I’m pretty sure I talked my parents into at least one more trip to both Popeye and Flash Gordon during this month. In the days before home video gave everything a quick turnaround, it was easier to convince my parents to see things several times in the theater. You sometimes had to wait for years before something was released, and the way I dealt with that was by seeing a favorite film as many times as I could while it was in release. I would do my best to internalize the film so that I could recall it later. Home video has definitely changed the way I process films, and it’s only because of home video that a project like this is even possible, but I miss that feeling that movies existed in a sacred space and you needed to see them in theaters or risk missing them forever.

JANUARY 2

The Man Who Saw Tomorrow

Orson Welles, Philip L. Clarke, Ray Laska, Bob Ruggiero, Roy Edmunds, Ray Chubb, Richard Butler, Jason Nesmith, Howard Ackerman, Brass Adams, Terry Clotiaux, David Burke, Bob Bigelow, Marji Martin, Thor Nielsen, Harry Bugin, Emile Hamaty, Dante Rochetti, Howard David, Charles Castilla, Ross Evans, Paul Valentine, Jeane Dixon, Charles Neilson Gattey, Kate Hutton, Edgar D. Mitchell

music by William Loose and Jack Tillar

screenplay by Robert Guenette and Alan Hopgood

produced by Paul Drane and Robert Guenette and Lee Kramer

directed by Robert Guenette

Rated PG

1 hr 30 mins

A “documentary” that digs into the predictions of Nostradamus and how accurate those predictions are.

Amazingly enough, this was distributed by Warner Bros., and it feels like one of the cheapest, shoddiest things they ever slapped their logo onto, a half-hearted attempt to make the case for Nostradamus as a genuine visionary.

Michel de Notredame, known to most as Nostradamus, was an astrologer and a physician who wrote a book full of quatrains that modern readers love to pretend predicted major world events. They did not, of course, and the reality is that his writing was intentionally vague, built on an understanding of history and the way cycles repeat themselves. Calling him psychic is akin to claiming that The Simpsons keeps predicting history because you don’t understand that The Simpsons takes aim at targets that, sadly, have not changed much in the last 23 years. Nostradamus, even at the time he wrote his prophecies, was often criticized as a fraud or a crank, a lazy astrologer at best. He also borrowed many of his prophecies from other places.

This film has no interest in interrogating the truth about him as a historical figure. David Wolper, the film’s executive producer, was quite open about the fact that he didn’t believe a word of the movie, as was narrator Orson Welles. They sell it all with straight faces, though, listing some of Nostradamus’s greatest hits and doing all they can to tie his vague predictions to very specific real-world events. Any original footage in the film is super-cheap, with all the aesthetic panache of the weakest episode of In Search Of, and overall, it feels like the definition of a cash grab.

I will say this about director Robert Guenette, though. Whether he ever knew it or not, he was quietly one of the most influential filmmakers of the last 45 years thanks to the behind-the-scenes specials he directed in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. The Making of Star Wars, SP FX: The Empire Strikes Back, Classic Creatures: Return of the Jedi, and Great Movie Stunts: Raiders of the Lost Ark were all specials that I taped off of TV and rewatched endlessly, and I’ve known many filmmakers over the years who got their first real look at what went into making a film thanks to Guenette’s work.

While there is an ocean of behind-the-scenes stuff produced these days, what made his work special was the access he had and the idea that there was no one else really doing it. He helped pull that curtain back and for young viewers like me, his work told us that filmmaking was a job, one that we might actually be able to do. How can I begrudge him his silly little Nostradamus film when that’s the case?

My American Uncle

Gérard Depardieu, Nicole Garcia, Roger Pierre, Nelly Borgeaud, Perre Arditi, Gérard Darrieu, Philippe Laudenbach, Marie Dubois, Henri Laborit, Bernard Malaterre, Laurence Roy, Alexandre Rignault, Véronique Silver, Jean Lescot, Geneviève Mnich, Maurice Gauthier, Guillaume Boisseau, Ina Bedart, Ludovic Salis, François Calvez, Stephanie Loustau, Monique Mauclair, Damien Boisseau, Gaston Vacchia, Bertrand Lepage, Jean-Philippe Puymartin, Catherine Frot, Valérie Dréville, Brigitte Roüan, Max Vialle, Yves Peneau, Jean-Bernard Guillard, Laurence Février, Charlotte Bonnet, Jean Dasté, Anne-Christine Joinneau, Sébastien Drai, Marjorie Godin, Lillane Gaudet, Isabelle Ganz, Maria Leborit, Albert Médina, Laurence Badie, Carène Ferrey, Sabine Thomas, Catherine Serra, Jacques Rispal, Héléna Manson, Serge Feuillard, Gilette Barbier, Dominique Rozan, Michael Muller

cinematography by Sacha Vierny

music by Arié Dzierlatka

screenplay by Jean Grualt

based on the writings of Henri Laborit

produced by Philippe Dussart

directed by Alain Resnais

Rated PG

2 hrs 5 mins

Acclaimed filmmaker Alain Resnais illuminates the ideas of French philosopher Henri Laborit by juxtaposing three different characters and their lives and attitudes.

Does that synopsis seem kind of vague? I challenge anyone to do better at summing up this truly unique picture in just a few sentences. I am unfamiliar with Henri Laborit and his work, but I’ve seen several other films by Alain Resnais, and that at least prepared me a bit for just how unconventional he is in his general approach.

If you’re unfamiliar with Resnais and his work, I would suggest Last Week In Marienbad as an entry point. If you watch that and enjoy it, then dig in deeper, but if you watch that and you bounce off of it, it doesn’t get any easier from there. Resnais loved to examine memory and fantasy and the way our subconscious is in constant dialogue with our consciousness and he built his films like elaborate games. He never comes directly at his themes or ideas, although his early work was largely in documentary shorts. It makes sense that he collaborated with Chris Marker, another boldly experimental storyteller who stood apart from the French New Wave in a number of key stylistic ways. One of the reasons his early film Night and Fog is so powerful is because he doesn’t approach shooting footage of the Nazi concentration camps like anyone else would. He was one of the first people to film them, and he didn’t approach it emotionally, knowing full well that the subject matter was already loaded with inherent emotion. It’s a bracing experience, unforgettable, and it justifiably launched him onto the international stage.

By the time he reached this film in 1980, he had already had his most influential period, struggled for most of a decade to get projects funded, and then made the jump to English-language for the first time. It makes sense that he would be drawn to the work of Laborit, an academic who rejected the rigor of academia because he worked in so many fields, believing that it was the broad nature of his inquisitions that gave them value. He made his early reputation working in the field of anesthesiology. Later, he moved into a broader study of psychotropics and their impact on memory, and he was a primary innovator in researching the impact of GHB.

Reading about him, I am still baffled how that background led to the work that Resnais adapted here, theories about animal behavior and how it relates to the human brain and various personality types. The film casts Gérard Depardieu, Nicole Garcia, and Roger Pierre as three radically different characters who each embody certain traits that Laborit wants to discuss. There’s not really a narrative here, but instead, you just watch behavior and Laborit talks about how their behavior relates to his theories. The characters intersect at different points as a way of putting stress on them and testing those behaviors. There’s also a fascinating thread where the characters (and the actors playing them) are contrasted with the classic French movie stars they most identify with, and it’s an interesting way to shorthand the way we see ourselves versus the way others see us. Ultimately, the film feels like it is about the way we live in our own brains and the dissonance that can exist between what we think and what we feel and how we allow that to drive us. I’m not sure I think the film is totally successful, but it does not feel like any other film I’ve ever seen, and that certainly counts for something.

Underground Aces

Dirk Benedict, T.K. Carter, Robert Hegyes, Rick Podell, Michael Winslow, Kario Salem, Ralph Seymour, Randy Brooks, Joshua Daniel, Sid Haig, Jerry Orbach, Melanie Griffith, Audrey Landers, Fawne Harriman, Mimi Maynard, Frank Gorshin, William Mims, Phil Adams, Marlena Amey, Jerry Anderson, Selma Archerd, James Bacon, Kathleen Bracken, Barbara Burroughs, Twink Caplan, Jade Clark, Steve Daron, Bob Drew, Lynda Farrell, Andrea Frierson, Gina Gallego, Sonny Gibson, Bob Harders, Sosimo Hernandez, Ernie Hudson, Nancy Jeris, Nicky Katt, Kellie Khristiansen, Jack Krupnick, Elli Maclure, Jock McNeil, Biff Maynard, Marsha Meyers, Sarah Miller, Jed Mills, Jonathan Moore, Yvonne Regalado, Four Scott, Bill Smillie, Rebecca Stanley, Johnny Venokur, Dru Wagner Harris

cinematography by Thomas Del Ruth

music by Pete Rugolo

screenplay by Lenore Wright and James Carabatsos and Andrew Peter Marin

produced by Jay Weston

directed by Robert Butler

Rated PG

1 hr 35 mins

An ensemble comedy about the valets who park cars for the Beverly Plaza hotel and the customers they encounter.

If there is a defining comedy of the ‘80s, it may be Police Academy, but that film didn’t happen in a vacuum. There were a number of movies that felt like dry runs for that eventual hit, and this particular one is packed with low-grade familiar faces from the ‘80s and even features Michael Winslow in a featured supporting role, pretty much doing exactly what Michael Winslow always does.

We’re at the point in this project where we are seeing directors show up for the second time. Robert Butler’s Night of the Juggler was released in May of 1980, and it’s a good grimy little thriller that feels like it stands apart from a lot of what Butler made.

I literally grew up watching his work, movies like The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes, Hot Lead & Cold Feet, and The Barefoot Executive. He had a light touch that made his Disney live-action films just a wee bit more nimble than some of the other stuff the studio churned out in that era, and while Underground Aces isn’t great, there is a certain amiable lightness to it that makes this feel like a Robert Butler film. Dirk Benedict is the new guy at the parking garage, and as soon as he shows up, he starts will-they/won’t-theying with Melanie Griffith. There’s a major subplot about Audrey Landers as a bride-to-be who becomes the object of infatuation for a Sheik played by Kario Salem, and there is a whole conversation to be had about the casual racism of pretty much every choice in that storyline including the casting of Sid Haig as Faoud, his main advisor. It’s amazing that the primary face on the poster is Robert Hegyes, best known as Epstein on Welcome Back, Kotter. This was his big shot at making the jump to the big screen, and it’s safe to say it was a whiff.

For the most part, what works here is the stuff that I find most appealing about Caddyshack, the stuff that just focuses on the mundanity of the job and the way people battle the boredom and indignity of those jobs. The best workplace comedies are the most specific ones, the ones that really tap into something honest and observed, and there are a few scenes here that feel like they came out of someone’s experience. You’ll recognize people like T.K. Carter, Jerry Orbach, and Frank Gorshin, who brings the same seedy hamminess to this that he does to his unnerving work in 1985’s Hot Resort.

I would not necessarily recommend this to anyone as some lost or forgotten gem, but if you’re tracing the evolution of the snob-vs-slobs/ensemble ‘80s comedy, this feels like one you can’t ignore as a very particular step along the way.

JANUARY 9

Breakthrough

Richard Burton, Rod Steiger, Helmut Griem, Klaus Löwistsch, Michael Parks, Werner Pocath, Véronique Vendell, Horst Janson, Joachim Hansen, Walter Ullrich, Dieter Schidor, Bruno Dietrich, Sonja Jeannine, Günter Clemens, Michael Büttner, Dieter B. Gerlach, Günter Meisner, Curd Jürgens, Robert Mitchum

cinematography by Tony Imi

music by Peter Thomas

screenplay by Peter Berneis and Tony Williamson

produced by Wolf C. Hartwig and Hubert Lukowski

directed by Andrew V. McLaglen

Rated PG

1 hr 55 mins

German and American officers collaborate to try to assassinate Adolf Hitler in the days after D-Day. Sort of.

Dreadful. This unofficial sequel to Sam Peckinpah’s Cross of Iron is pretty much a disaster on all fronts, and it genuinely shocks me to see Andrew V. McLaglen is the director of it.

If you haven’t seen Cross of Iron, you should. It’s a really solid late-era Peckinpah picture with a terrific lead performance by James Coburn as a Wermacht soldier and a supporting cast including James Mason, David Warner and Maximillian Schell. It doesn’t really cover any new ground as a war movie, but it does put the audience in the shoes of an ordinary enlisted soldier in a way I find admirable. Like many films that are ostensibly anti-war, Cross of Iron seems awfully infatuated with the actual tactile thrills of combat, something Peckinpah was unable to resist.

McLaglen, on the other hand, thoroughly resists the temptation. He doesn’t glamorize the combat at all. Hell, he barely gives it a pulse, which is surprising. McLaglen isn’t the same kind of personal stylist as Peckinpah and brings less authorial voice to his work, but he was a reliable action director who made plenty of good films, and this feels especially disappointing in the midst of movies like The Wild Geese, The Sea Wolves, and ffolkes, which we discussed in April of 1980.

It feels like McLaglen is asleep at the wheel here, and it doesn’t help that his leads feel like the wax figure versions of themselves. Richard Burton steps in for Coburn here, and he is woefully miscast here. McLaglen worked with lots of older character actors at a similar point in their career and got good work out of them, but Robert Mitchum, Curt Jurgens, and Rod Steiger are just as adrift as Burton is, so I’m not sure who to blame. The script stinks, and if you like Cross of Iron at all, it’s a baffling follow-up. Steiner and Stansky, the duo whose constant back and forth antagonism drives everything about that film, are both back for this film, but now their relationship makes no sense at all.

While the synopsis for this film makes it sound like a “man on a mission” movie with a clean through-line, it’s not. This thing meanders and drags and characters do things for no discernible reasons and everyone looks tired and McLaglen leans on a surprising amount of stock footage for his action and it all just feels so goddamn cheap. Avoid at all costs.

JANUARY 16

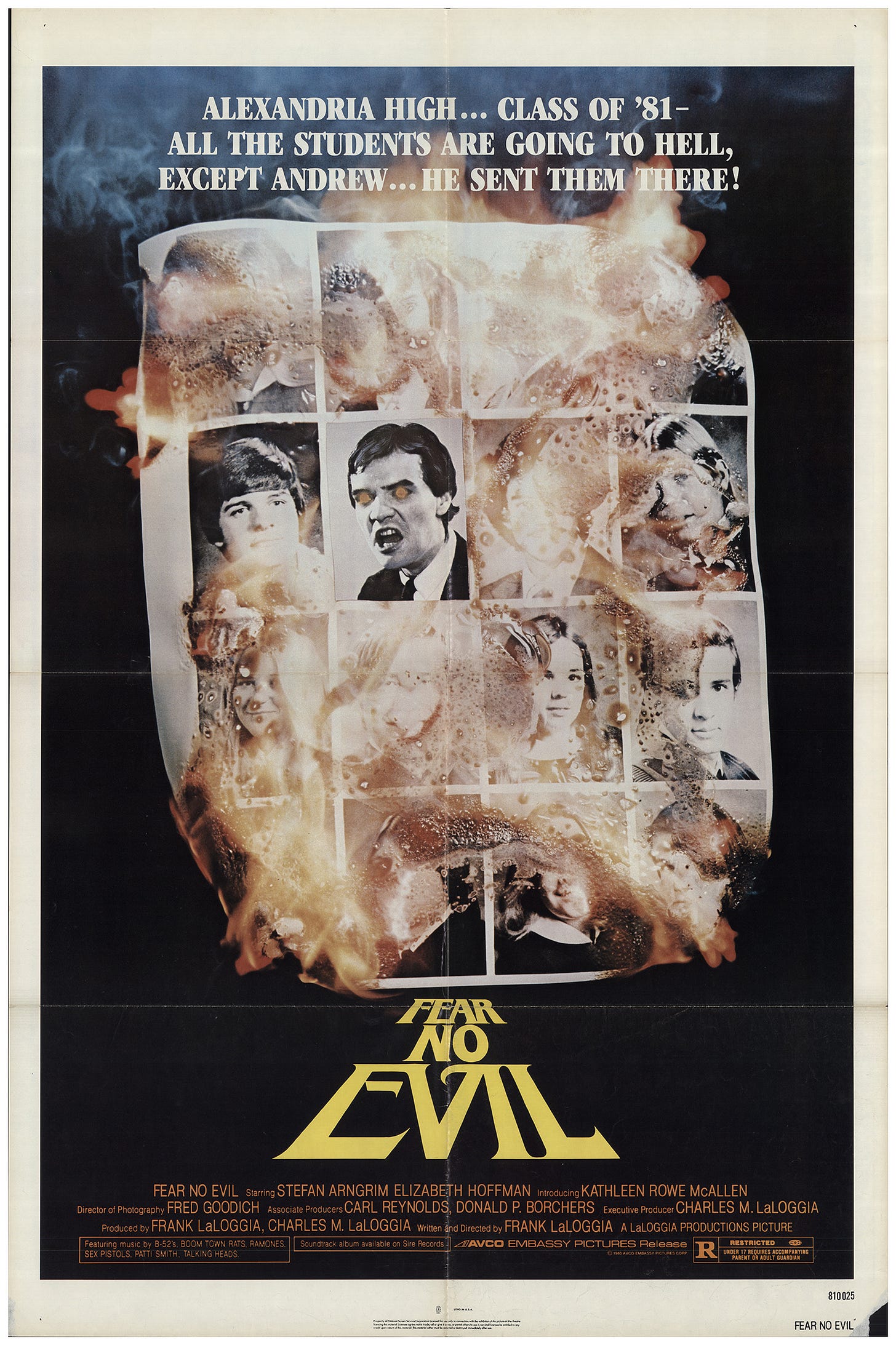

Fear No Evil

Stefan Arngrim, Elizabeth Hoffman, Kathleen Rowe McAllen, Frank Birney, Daniel Eden, John Holland, Barry Cooper, Alice Sachs, Paul Haber, Roslyn Gugino, Richard Jay Silverthorn, Marianne Simpson, Joyce Bumpus, Patricia Decillis, Chris DeVincentis, Malcolm Hegge, Robert Kuhn, Don O’Neil, Deanie Gordon, Philip E. Roy, Alexandra Cleveland, Jeff Richter, Pam Morris, Toby Gold, Dick Burt, Frank C. Montesanto, Melissa Rodgers, Baby Fisher, Joe Lalogga, Brian Coughlin, Michael Dewind, Gregory Houston, Wolfgang Voise, Paul Volta, Michael Paul Richard, Michael Olivier, Wayne Gaiteri, John Quinn, Howard Fernandez, Mary Tomassetti, Jennifer Sue Brooks, Jeffrey Sanzel, Mike Pascucci, Bill Brown, Marty Lombard, Fred Pari, Eddie West, Frank Montesanto Jr.

cinematography by Fred Goodich

music by Frank LaLoggia and David Spear

screenplay by Frank LaLoggia

produced by Frank LaLoggia

directed by Frank LaLoggia

Rated R

1 hr 39 mins

Two archangels are sent to earth to stop Satan from coming to power on Earth via a high school kid named Andrew.

Frank LaLoggia only made a few films, and he was as independent as you can be for both of them. The difference in how the films turned out appears to be largely due to his level of experience on the first film and the distributors he signed to handle each of the pictures.

His first experience, Fear No Evil, is definitely the lesser of his two films, but there is a degree of promise to the filmmaking that is noteworthy, even if it doesn’t really come together. He and his cousin Charles raised the money for the film and then came up just a little bit short when it came time for post-production. What they made was strong enough to get Avco’s attention, and when Avco bought the distribution rights to the film, they also took control of finishing the film. LaLoggia didn’t like the final film, and it’s easy to see why.

Clearly made to take advantage of the demonic possession/Satan cycle that was supercharged by the success of The Exorcist and The Omen, smashed together with a smattering of Carrie, this opens with a Catholic priest murdering a man outside of a castle. The location was actually baked into the financing for the film. They had to shoot at least part of it at the Boldt Castle in the Thousand Islands in New York, so the film opens and closes there, and there’s a certain degree of production value that LaLoggia gets from the location. The film itself is about Lucifer’s efforts to be born in human form on Earth. The first attempt we see is stopped, and then we cut to a few decades later and the baptism of baby Andrew, which ends, as do all good horror movie baptisms, with blood. We get to watch Andrew grow up in montage and then catch up with him in high school in the form of Stefan Arngrim, a shy honor student who is viciously bullied for being gay. Like Nightmare on Elm Street 2, this is homophobia horror, a film that is as much about the fear of being called gay in the ‘80s as it is about the fear of the Devil.

The reason the film doesn’t work is that it never quite picks a lane. It’s not outrageous enough to be a camp classic and it’s not scary enough to really work as horror. It’s a film that feels too restrained for a story that includes resurrected archangels, truly wild gender politics, and a combination Passion Play and prom dance, and that’s a shame. It feels like LaLoggia could have made something great out of this if he’d had the right support, and even in this hobbled form, there are things to be impressed by here, including the amazing soundtrack and the special effects by Peter Kuran. When we talk about queer horror in the ‘80s (and we will), this feels like one of the first films that can legitimately make the claim that it is text, not subtext, and certainly not accidental. I just wish it worked better as a coherent whole.

Fish Hawk

Will Sampson, Don Francks, Charles Fields, Mary Pirie, Chris Wiggins, Geoffrey Bowes, Arnie Achtman, Karen Austin, Kay Hawtrey, Ken James, Mavor Moore, Allan Royal, Les Rubie, Murray Westgate, Michael J. Reynolds

cinematography by René Verzier

music by Samuel Matlovsky

screenplay by Blanche Hanalis

based on the novel Old Fish Hawk by Mitchell Jayne

produced by Jon Slan

directed by Donald Shebib

Rated G

1 hr 34 mins

An unlikely friendship between an alcoholic older Native American man and a young white boy turns out to be important for both of them.

While it’s nice to see Will Sampson, best known for his work in One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest, play a leading role in a film, this is a Canadian family film that plays like someone thought live-action Disney adventures were too scary and thrilling, a total sleeping pill that takes ostensibly interesting subject matter and renders it totally toothless.

Donald Shebib was a promising independent Canadian director, and both Goin’ Down the Road and Between Friends were considered significant, thrilling examples of a new voice. Fish Hawk feels like he decided to prove he could also do mainstream family entertainment, but unfortunately, this does not make that case persuasively. The film is told in broad stereotypes, and even if it’s well-meaning, the film is breathtakingly dull. There’s an early moment when Fish Hawk’s dog is killed by a bear, and it’s probably the most thrilling moment in the movie. For the most part, this is a film where cartoonishly terrible white people abuse the sainted Indian until they realize they’re wrong and then they reveal that they were actually good people all along.

There is something well-intentioned about the film, but the execution falls way short of the idea, and we’ve seen plenty of films since that got much closer to this film’s target. Shebib actually directed a film we’ll get to in 1983 that does a nice job of telling a real-life Native American story that feels honestly observed, which only makes this more frustrating. Charlie Fields is a hammy kid actor, and he feels like a kid from 1978, not a kid from 1878. The same is true of the photography. At the very least, a film like this should lean heavily on the production value you get from shooting in nature, but this is bright and garish and ugly. It looks like a TV movie, and there’s something plastic about the entire endeavor. I hate beating up little movies in this newsletter, but there’s a reason you don’t know this one.

Hawk The Slayer

Jack Palance, John Terry, Bernard Bresslaw, Ray Charleson, Peter O’Farrell, William Morgan Sheppard, Patricia Quinn, Cheryl Campbell, Annette Crosbie, Catriona MacColl, Shane Briant, Harry Andrews, Christopher Benjamin, Roy Kinnear, Patrick Magee, Ferdy Mayne, Graham Stark, Warren Clarke, Declan Mulholland, Derrick O’Connor, Peter Benson, Maurice Colbourne, Barry Stokes, Anthony Milner, John J. Carney, Robert Putt, Stephen Rayne, Ken Parry, Lindsey Brook, Eddie Stacey, Jo England, Frankie Cosgrave, Melissa Wiltsie, Mark Cooper

cinematography by Paul Beeson

music by Harry Robinson

screenplay by Terry Marcel & Harry Robertson

produced by Harry Robertson

directed by Terry Marcel

Rated PG

1 hr 30 mins

A young man inherits a magic sword and sets out to avenge his father’s death at the hands of his brother.

Star Wars made everyone crazy. Audiences, sure, but filmmakers, too. Watching people chase that film’s success and attempt to deconstruct how to reproduce it was fascinating, and the most remarkable part is that it’s still happening a solid 45 years later. Hawk the Slayer landed, timing-wise, smack-dab between Star Wars and Conan The Barbarian, another film that absolutely warped the gravity of the film industry simply by existing. Even before Conan hit theaters, it inspired a wave of sword-and-sorcery films as people around the globe tried to cash in on what they saw as the next big thing. In the UK, I would imagine it was the news of John Boorman’s Excalibur that made it possible for Terry Marcel to get this film bankrolled in the short term, but everyone was hoping they might catch hold of that next thing that would drive kids around the world absolutely batty.

Hawk the Slayer is far more Star Wars than Conan and suffers from one of the biggest problems that most post-Star Wars fantasy suffers from, a smothering cascade of exposition instead of character. Hawk (John Terry) and Voltan (Jack Palance) are the brothers who find themselves sitting on opposite sides of the good/evil table after Voltan murders their father, and there are certainly more compelling stories that feature the same basic set-up as Hawk the Slayer. For some reason, most likely budgetary, this epic sprawling adventure film takes place in what feels like about 500 square yards of a forest, even though it takes place over years and years of narrative real estate. Even though the film is only 90 minutes, it manages to meander a surprising amount, dragging ass after an opening scene that basically picks up at the last possible moment. Hawk picks up a fistful of buddies to help him… do stuff… before the film finally lurches into something like a point near the end, and every one of them feels like they are so lazily borrowed from Tolkien and his imitators that the dwarf might as well be named Shmimli. It’s just a carbon copy of a carbon copy of a carbon copy, which is wild considering how early this is in the overall sword-and-sorcery cycle. I liked seeing Patricia Quinn of Rocky Horror Picture Show fame show up as a witch, but it’s not like anyone really gets to shine here. The best you can say about any of these performances is that everyone is in frame and speaking the correct language. Even Palance can’t make his scenery-chewing fun, and John Terry is a block of wood, as dull a hero as we’ll see this decade. No one’s terrible, but in a film like this, with such a thin script and such perfunctory direction, that’s the most anyone’s able to pull off.

Marcel exhibits no natural flair for storytelling here, and under his direction, pretty much every single tech department shits the bed in spectacular fashion. It is an ugly film, poorly lit, and the effects feel like they can’t even compete with the worst of what was happening on Doctor Who at the time, much less with the best of what was being done for movies. Maybe the most cynical thing about the entire enterprise is their dangling threat of a sequel at the end. I know Terry Marcel has attempted to make that threat a reality over the years, but I can’t imagine what purpose it would serve based on just how hollow an endeavor this is.

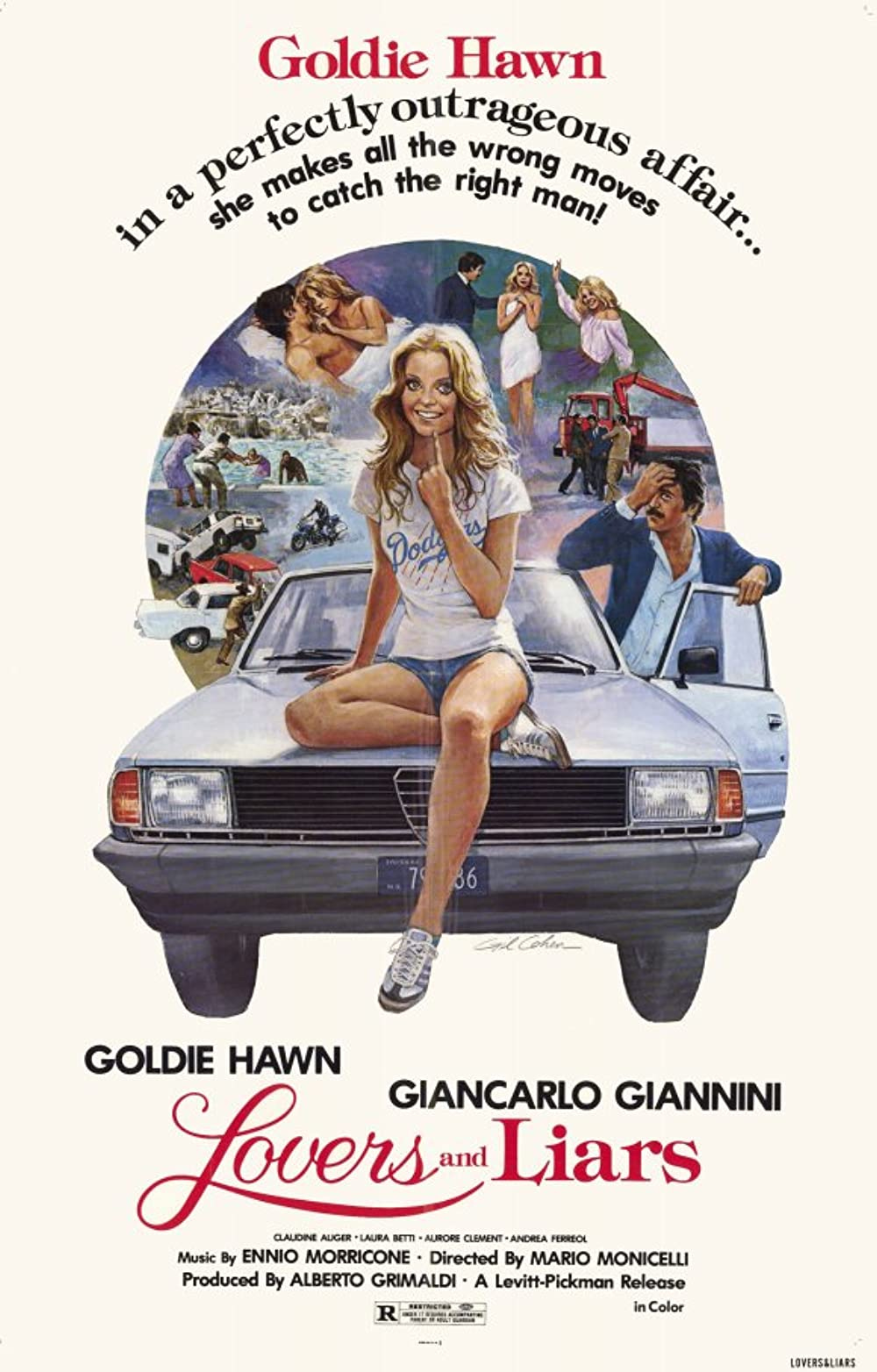

Lovers and Liars

Goldie Hawn, Giancarlo Giannini, Claudine Auger, Aurore Clément, Laura Betti, Andréa Ferréol, Lorraine De Selle, Renzo Montagnani, Gino Santercole

cinematography by Tonino Delli Colli

music by Ennio Morricone

screenplay by Leonardo Benvenuti, Piero De Bernardi, Mario Monicelli and Paul D. Zimmerman

story by Tullio Pinelli

produced by Alberto Grimaldi

directed by Mario Monicelli

Rated R

2 hrs

A young American tourist takes a road trip with an Italian stranger and sparks allegedly fly.

When is a Goldie Hawn film not a Goldie Hawn film?

Maybe when it’s shot in Italy and then shelved for a few years, only to be dumped into theaters to try to capitalize on a little bit of heat after Private Benjamin and Seems Like Old Times both did so well at the box office. Technically, yes, Goldie Hawn is one of the two stars of this absolutely comatose romantic trifle, alongside Giancarlo Giannini, but there’s nothing here that hints at the carefully crafted comic persona that made Hawn a star in the first place.

She plays an American who is staying with a friend in Rome. Her friend’s having an affair with a married man, and one day, he shows up at the apartment, evidently all horned up because his father is dying. The friend isn’t interested, but Anita (Hawn) decides to catch a ride with Guido (Giannini) to Pisa where he’s going to see his father. There’s no chemistry between them and no logical reason she’d take a ride from him, but that’s the set-up, and the film is determined to milk whatever tension they can out of it.

There’s a breezy quality to the best European comedies, and clearly, this film wants to be that kind of light and nimble and sexy concoction, but nothing happens. The road trip is a total snooze and there’s no attempt to expand either of them beyond those first impressions of them as characters. Beyond that, it feels cheap and shoddy, poorly dubbed for everyone, and it can’t even offer a surface-level sexiness.

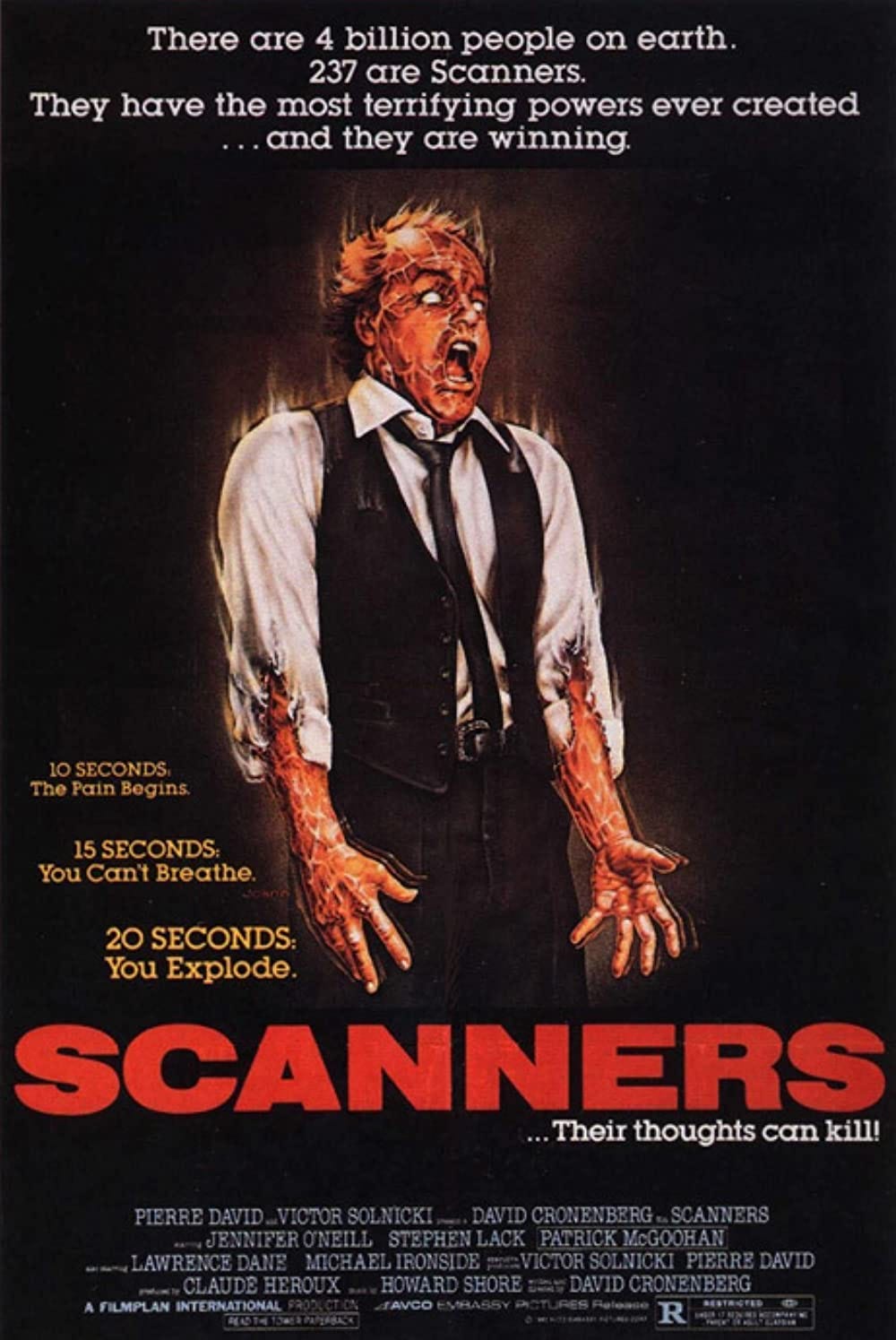

Scanners

Jennifer O’Neill, Stephen Lack, Patrick McGoohan, Lawrence Dane, Michael Ironside, Robert A. Silverman, Lee Broker, Mavor Moore, Adam Ludwig, Murray Cruchley, Fred Doederlein, Géza Kovács, Sonny Forbes, Jérôme Tiberghien, Denis Lacroix, Elizabeth Mudry, Victor Désy, Louis Del Grande, Anthony Sherwood, Ken Umland, Anne Anglin, Jock Brandis, Jack Messinger, Victor Knight, Karen Fullerton, Margaret Gadbois, Terrance P. Coady, Steve Michaels, Malcolm Nelthorpe, Nicholas Kilbertus, Don Buchsbaum, Roland Nincheri, Kimberly McKeever, Robert Boyd, Graham Batchelor, Dean Hagopian, Alex Stevens, Neil Affleck

cinematography by Mark Irwin

music by Howard Shore

screenplay by David Cronenberg

produced by Claude Héroux

directed by David Cronenberg

Rated R

1 hr 43 mins

A homeless man is recruited into a secret program to fight a powerful psychic.

If I’m being totally honest, Scanners might be one of the most directly influential films on my own writing career, and yet I somehow forget that when I haven’t seen the film in a while.

I suspect I’m not alone. You can see the basic shape of Scanners in a ton of pop culture storytelling today, and not just in America. There are anime directors who clearly saw and adored Cronenberg’s movie, too, and there are novelists who have internalized some of the ideas and attitudes of the film. It’s one of those movies that has left an outsized fingerprint in terms of influence, and there is something irresistible about the key imagery from the film even if it’s not Cronenberg’s strongest by a long shot. The film opens with a homeless guy played by Stephen Lack at a Toronto mall. Some women sitting nearby start talking about him, clearly disgusted by him, and he starts to get upset. Something happens, though, and his reaction somehow takes hold of one of the women, causing her to have a seizure. He gets up to leave and some guys start to chase him, eventually tranquilizing him and taking him prisoner.

If you know anything about Scanners, you probably know the most iconic image, a scene that happens about a half-hour into the film. There’s a demonstration for a roomful of people by ConSec, a military contractor that controls Scanners, people with valuable psychic powers. There’s a Scanner who is going to read someone from the crowd, and Darryl Revok (Michael Ironside) volunteers to be the test subject. It turns out that Darryl is a Scanner himself, a much more powerful one, and he’s infiltrated so that he can hold a little demonstration of his own. He enters into a mental struggle with the company’s Scanner, and after a bit of back and forth, the other guy’s head explodes in one of the most memorable make-up effects in movie history. In general, Dick Smith’s make-up work is only featured in a few key moments, but the impact it has had on the collective imagination is immeasurable. I love the climactic battle and the weird way Smith uses the bladder effects. There are few things I’ve ever seen in a movie that look more painful than what Darryl and Cameron (Lack) go through.

The film came at a pivotal moment in Cronenberg’s career. He had definitely started to make some noise internationally. People were paying attention, and The Brood in particular had been devoured by horror fans. He took several of his early scripts and incorporated ideas from them into the story of these strange mutations waging a war of psychic abilities in secret. By this point, Chris Claremont’s era of “the all-new, all-different X-Men” was already well underway, so it’s not like Cronenberg’s ideas are particularly revolutionary or unheard of. I have no idea if he was aware of those comics or not, but the ideas were already part of the science-fiction world as well thanks to texts like Theodore Sturgeon’s More Than Human. All of this happens along a sort of pop culture evolutionary ladder, and what makes Cronenberg’s film such a notable and iconic point on that larger timeline is the power of that imagery.

It’s certainly not the lead performance by Stephen Lack, who is a blank. That sort of works at times. When we meet Cameron, like I said, he’s living on the street and confused about where he is and barely able to function. After he wakes up at ConSec, he works with Dr. Paul Ruth (Patrick McGoohan) to get a handle on his powers. He was the one who caused the woman’s seizure even if he didn’t understand what he was doing or how he was doing it. Ruth explains that Cameron is one of less than 300 people on the planet who has his kind of abilities, and he tells him that they’ve developed a drug that helps Scanners suppress their abilities. He’s able to help Cameron finally tune out the voices in his head, the voices of all the people around him, and it gives Cameron peace for the first time ever. Ruth tells him that they need his help because Darryl Revok, who we saw attack one of ConSec’s men, is coming for every other Scanner for some reason.

Of course ConSec is full of shit and there’s more going on than they’re telling Cameron, and overall, I think Cronenberg’s script is a fairly lean and nasty little thriller. The problem is that once Cameron’s starting to get better as a person, there’s no difference in the way Lack plays him. Lack has these huge striking blue eyes and I can see why Cronenberg cast him. He’s great as long as he doesn’t have to deliver any dialogue, and a lot of his performance is handled silently. My question is how much of that is because Cronenberg realized that Lack is enormously limited as a performer after it was too late to recast him. It doesn’t help that Revok is played by a young Michael Ironside, and he’s electrifying in every single second of screen time. It doesn’t matter if he’s battling another Scanner or if we’re watching old footage of the tests they did on him or if he’s just in a meeting… you can’t look at anything but Ironside every time he’s onscreen. By the time Cameron and Darryl come face to the face at the end of the film, I always find myself rooting for Darryl, and not just because of Lack’s powerful charisma deficit. He’s one of those movie villains who is definitely wrong but who is also so clearly wronged in the first place and so justifiably angry that it almost unbalances the film.

The film taps into a general distrust of authority and a fear of what Big Pharma is doing to us, and one of the things I love about how Cronenberg tells this story is the way it illuminates the way genre is often a matter of voice, not subject matter. You tell this same story with a slightly different focus and you get X-Men: First Class. Tell it a slightly different way and it’s Akira. Cronenberg has been fairly adamant that he doesn’t want to see a remake, and I ignore all of the tax-shelter sequels that were cranked out without his participation. I do think he created one of his more interesting worlds here, though, and easily could have expanded on the story. We only meet a few of the 237 Scanners that supposedly exist, and thanks to Ephemerol, you’ve got a mechanism to create as many new Scanners as you want. He tells one particular story here, and it feels like an origin point for something larger, but I respect that he didn’t keep going back to the well. He strikes me as someone who is much happier suggesting a larger canvass than actually having to fill in every inch of it. I’ve always loved his ability to imply the apocalypse using nothing more than an apartment building in Toronto, and this might be the best example of that. His regular collaborators Mark Irwin and Howard Shore help define his aesthetic, and their work here definitely feels like everyone’s getting better and better at evoking this particular thing they’re doing. It also feels like the last of his small Canadian films, and maybe that’s part of my outsized affection for it as well. This is the end of what feels like the “original” Cronenberg, and part of me wishes he’d spent his entire career making these miniature epics all over Canada because of just how special and singular they remain.

JANUARY 23

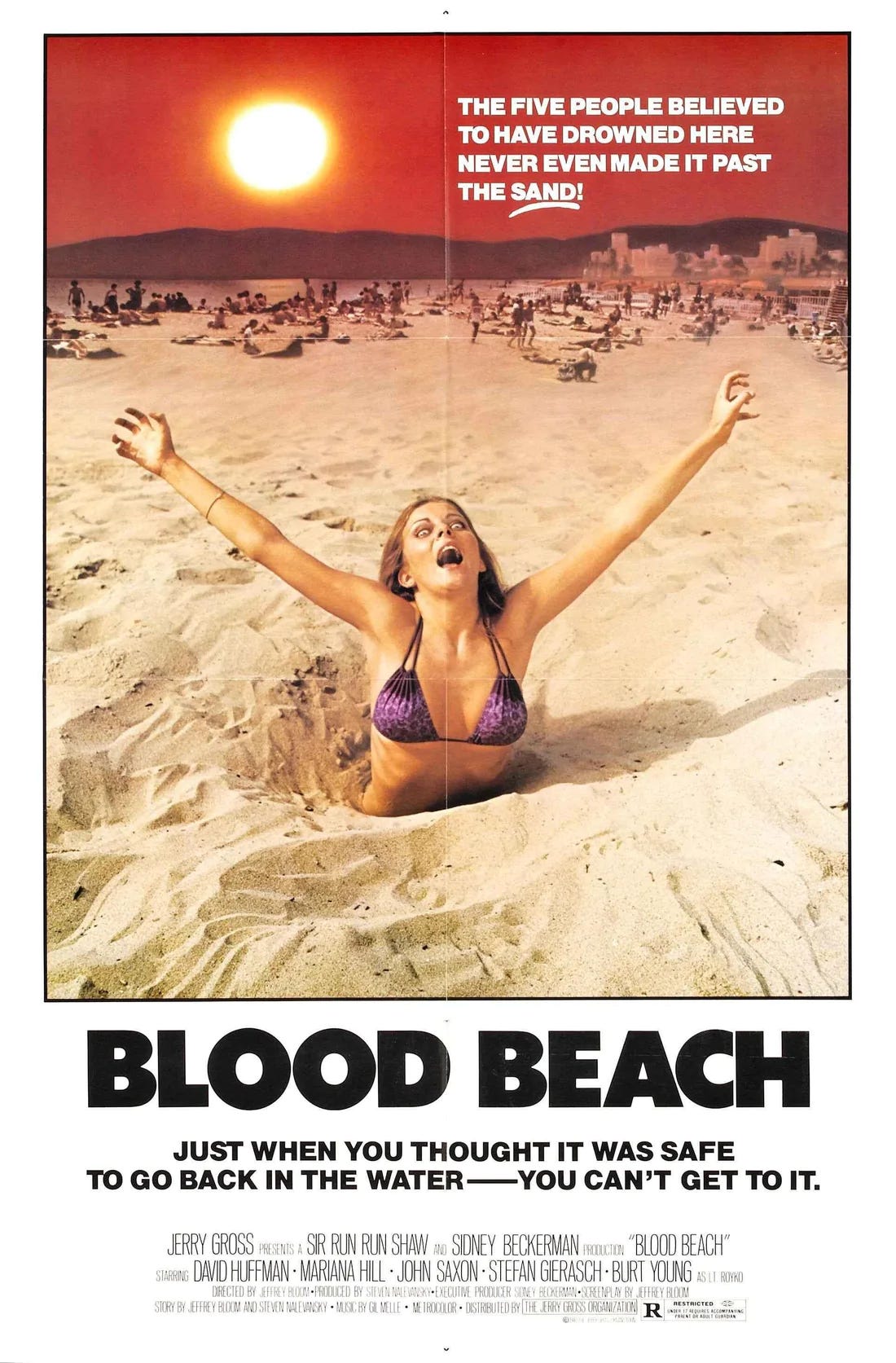

Blood Beach

David Huffman, Marianna Hill, Burt Young, Otis Young, Lena Pousette, John Saxon, Darrell Fetty, Stefan Gierasch, Eleanor Zee, Pamela McMyler, Harriet Medin, Mickey Fox, Laura Burkett, Marleta Giles, Jacqueline Randall, Don Barlow, David Wysong, Charles Rowe Rook, John Joseph Thomas, Julie Dolan, Sandra Friebel, Christopher Franklin, Bobby Bass, Reed Morgan, Barney Pell, Marcus Chong, Mary Jo Catlett, Ian Ambercrombie, Robert Newirth, Lavelle Roby, Jimmy Ogg, Lynne Fienerman, Steve Finkel, David Jacob, Stefanie Auerbach, Steve Ballard, Judy Walker, Muriel Bakcha, Lynne Marta

cinematography by Steven Poster

music by Gil Mellé

screenplay by Jeffrey Bloom

story by Jeffrey Bloom and Steven Nalavansky

produced by Steven Nalavansky

directed by Jeffrey Bloom

Rated R

1 hr 32 mins

A monster living beneath the sand starts eating people on Santa Monica Beach.

There are a few moments in this film where it lurches to life and you get a glimpse of the fun, unapologetic exploitation film it could have been. Unfortunately, there are not enough of them.

That poster promises something fun. A movie about monsters that live under the sand of a Santa Monica beach, eating people, is fun. You’ve got John Saxon, Burt Young, and Otis Young (no relation) all starring. Fun, right? So why isn’t the film actually fun? For one thing, it’s way too focused on the cops who are investigating the disappearances. This movie shamelessly borrows from Jaws, among other sources, and the movie’s opening scene is a clever inversion of what we expect based on Jaws. A lady sits on the beach watching a man go out for a moonlight swim, but instead of him getting attacked, she’s the one who gets eaten by something that pulls her under the sand, leaving her dog behind. This sets up a running joke that we’ll see duplicated by Blake Edwards in S.O.B., and it establishes Harry (David Huffman), the guy who went swimming, as our lead.

It’s a film that leans on monster-movie cliche, but it is not entirely without merit. There’s something brute-force-effective about the image of a person being eaten by the sand, and director Jeffrey Bloom stages those scenes well. I like the actual design of the monster and I think the film wisely holds the reveal until the right moment. But with a human cast this packed with solid character actors, this should be more fun in-between the monster moments, and it’s not. It’s clear that the actors are all trying, doing everything they can, and whatever joy there is to be found in the the majority of the film comes down to Bloom letting his actors riff off each other. This feel ultra low-budget and I’m guessing the majority of the $2 million budget was just locking down actors you recognized. If you find the poster and the premise irresistible, Blood Beach isn’t awful, but I can’t really call it a good film, either.

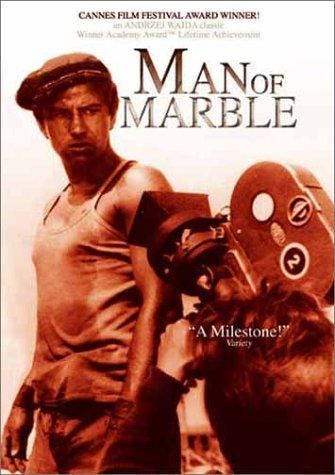

Man of Marble

Jerzy Radziwillowicz, Krystyna Janda, Tadeusz Lomnicki, Jacek Lomnicki, Michal Tarkowski, Piotr Cieslak, Wieslaw Wójcik, Krystyna Zachwatowicz, Magda Teresa Wójcik, Boguslaw Sobczuk, Leonard Zajaczkowski, Jacek Domanski, Irena Laskowska, Zdzislaw Kozien, Wieslaw Drzewicz, Kazmierz Kaczor, Ewa Zietek

cinematography by Edward Klosinski

music by Andrzej Korzynski

screenplay by Aleksander Scibor-Rylski

produced by Andrzej Wajda

directed by Andrzej Wajda

not rated

2 hrs 40 mins

A young woman sets out to make a documentary about a nearly-forgotten folk hero from the Stalinist era.

Although this was made in 1977, it took several years for the film to find American distribution, and looking at it today, it seems like an impossible commercial prospect. The film’s sequel, Man of Iron, won the Palme d’Or at Cannes in the summer of 1981, which may have finally motivated distributors to take a chance on this one. It is a film that uses the language of documentary and propaganda to tell a fictional story that props up a Stalinist hero as a way of directly criticizing Soviet socialism. It is also a film that is deeply wired into the politics of the Soviet Union in the 20th century and it expects that you understand certain contextual things. If you don’t, the film must feel inpeneterable.

That’s the point, though. Andrzej Wajda was making Polish movies about Polish ideas and wasn’t particularly interested in diluting those ideas in order to make them more internationally accessible. You can’t fault international filmmakers for constantly thinking about the American market and how their work might play there. We’ve built a system where success in America is seen as “real” success for a film, and there are plenty of filmmakers who seemed like they were almost auditioning with their early work, determined to move to America to work in the studio system as soon as possible. That’s not what this feels like. This is a film about Poland’s place in the Stalinist era and the way ideas were (or, more importantly, weren’t) expressed during that era. It took him almost 20 years to make the film after he first had the idea, and even when he did make it, the film was incredibly difficult to get into theaters and in front of viewers.

Krystyna Janda stars as Agnieszka, a film student who is getting ready to graduate from school. She’s got one last project to complete, and her big idea is tracking down Mateusz Birkut (Jerzy Radziwilowicz), a bricklayer who was a potent unifying symbol of Stakhanovite power. He vanished during the de-Stalinization era, and no one’s really sure what happened. As Agnieska begins her research, interviewing people from Birkut’s life, there is a bleak, wicked sense of humor that underscores a lot of what we’re watching. The Birkut that people describe doesn’t really match the portrait that was sold to the public, and that’s really the point of the exercise. Wadja grew up in a Poland that told a certain story about itself, and his films were an attempt to make sense of that story as compared to the reality that Wadja experienced. Eventually, Agnieska gets an education in how propaganda was manufactured and how Birkut the person was almost irrelevant to Birkut the symbol. The film eventually reaches a point where Agnieska realizes that she’s never going to be able to tell the story that she’s been researching, and the resolution she reaches instead puts a human face on this larger-than-life story. There is hope built into this movie, and considering when the movie was made, it’s fascinating to see the way this drops the seeds that Wadja was able to pick up in Man of Iron. Taken together, these movies feel like they paint a very specific and human picture of a pivotal moment in the history of Poland and the rise of the Solidarity union movement.

This is a dense and difficult film and I did some reading to try to make sense of the context of it all. Even so, I think it’s a movie that is so impressively made, so audacious as an act of political literature from within a repressive regime, that it is something every film fan should wrestle with at some point. I’ve seen this referred to as the Polish Citizen Kane, and there’s certainly a superficial resemblance in terms of how this portrait of a person is contructed through interviews and archival footage and memory, but Wadja has a powerful, vital voice that is entirely his own. This is a film that could only have been made by one person at one time in one place, and it feels wholly miraculous that it was allowed to exist at all, much less to escape to a larger stage where its message was received so loud and clear.

Napoleon (limited release)

Albert Dieudonné, Vladamir Roudenko, Edmond Van Daële, Alexandre Koubitzky, Antonin Artaud, Abel Gance, Gina Manès, Suzanne Bianchetti, Marguerite Gance, Yvette Dieudonné, Philippe Hériat, Pierre Batcheff, Eugénie Buffet, Acho Chakatouny, Nicolas Koline, Max Maxudian, Annabella, Henri Baudin, Alex Bernard, Roger Blum, Daniel Buiret, Georges Cahuzac, Adrien Caillard, Pierre de Canolle, Carrie Carvalho, Sylvio Cavicchia, Léon Courtois, Gilbert Dacheux, Damia, Pierre Danis, W. Percy Day, Raoul De Ansorena, Boris de Fast, Favière, Serge Freddy-Karl, Jean Guadrey, Simone Genevois, Georges Hénin, Jean Henry, Henry Krauss, Harry Krimer, Georges Lampin, Alexandre Mathillon, Genica Missirio, Francine Mussey, Jeanne Pen, Roblin, Jack Rye, Louis Sance, Maurice Schutz, Andrée Standart, Suzy Vernon, Petit Vidal, Robert Vidalin, Louis Vonelly, Jean d’Yd, René Jeanne, Lomon, Florence Talma, François Viguier, Raoul Villiers, Michel Zahar

cinematography by Léonce-Henri Burel, Jules Kruger, Joseph-Louis Mundwiller and Nikolai Toporkoff

music by Carmine Coppola and Carl Davis

screenplay by Abel Gance

produced by Henri de Cazotte

directed by Abel Gance

not rated

5 hrs 30 mins

Abel Gance’s silent epic telling of Napoleon’s early years, from childhood through his successful invasion of Italy.

Kevin Brownlow has spent most of his life restoring Abel Gance’s Napoleon. His work as a film historian is impeccable, and his focus on the silent era is important. His massive 13-part documentary series Hollywood is an excellent primer on silent cinema, and he at 84, the breadth of his body of work is truly staggering. Not many critics/historians leave such a large thumbprint on their favorite art form, and fewer still can be said to have actually rescued a movie as inarguably as Brownlow rescued this one.

His fascination with the movie began in childhood and he worked for years to find the original materials and to help reconstruct Gance’s proposed vision of presenting the film in Polyvision, a format that involved three screens and three projectors during certain key sequences. The film (which runs five-and-a-half hours in its fully-restored glory) represented the culmination of his life’s work up to that point, and Francis Coppola was involved in getting the restoration into theaters as an actual commercial release. The first version was shown in Telluride in 1979, and then tweaked at a few more festival appearances before the restoration officially opened at Radio City Music Hall in New York. Each performance featured a live orchestra performing Carmine Coppola’s newly-composed score, and the entire run played to sold-out houses. Gance was able to live long enough to see the restoration and a reassessment of his work overall, but Brownlow’s work continued. Each time there were new scenes discovered in archives somewhere, Brownlow worked to restore them to their proper place in the film. Even so, the gulf between this and the nine-hour version that originally played in the ‘20s for just a few brief appearances, remains insurmountable. This is still just a suggestion of what Gance originally intended, which is mind-boggling even in truncated form.

Napoleon is a massive meal of a movie, originally conceived as the first in a series of six movies, and I can’t imagine what he was going to do over the course of six films if this is the scale of what would essentially just be the opening act. It’s a movie that paints in big emotion, a movie about spectacle and sweeping romance, and you can feel the exuberance of Abel Gance helping to invent the actual language of visual storytelling at every turn. It is easy to dismiss films from almost 100 years ago as “dated,” but in terms of sheer visual invention, the film feels almost experimental. Albert Dieudonné plays Napoleon for most of the film (it starts when he’s still just a child) and he gives a remarkable performance, full of nuance and incredibly controlled. By the time the film builds to its epic conclusion, where it fully embraces the possibilities of montage and multiple screens, he has started to grow into the man who could easily command an army, and Gance makes this all feel rousing and urgent.

This is not an easy film to see, even today, and it defies pretty much every rule of structure that we’ve had drilled into us by decades and decades of commercial cinema. But for anyone who finds themselves intoxicated by pure, unabashed expressions of the potential of cinema, Napoleon remains a nearly-singular experience, an early signpost for the limitless ways in which we can turn this remarkable art form to the task of telling any story.

JANUARY 30

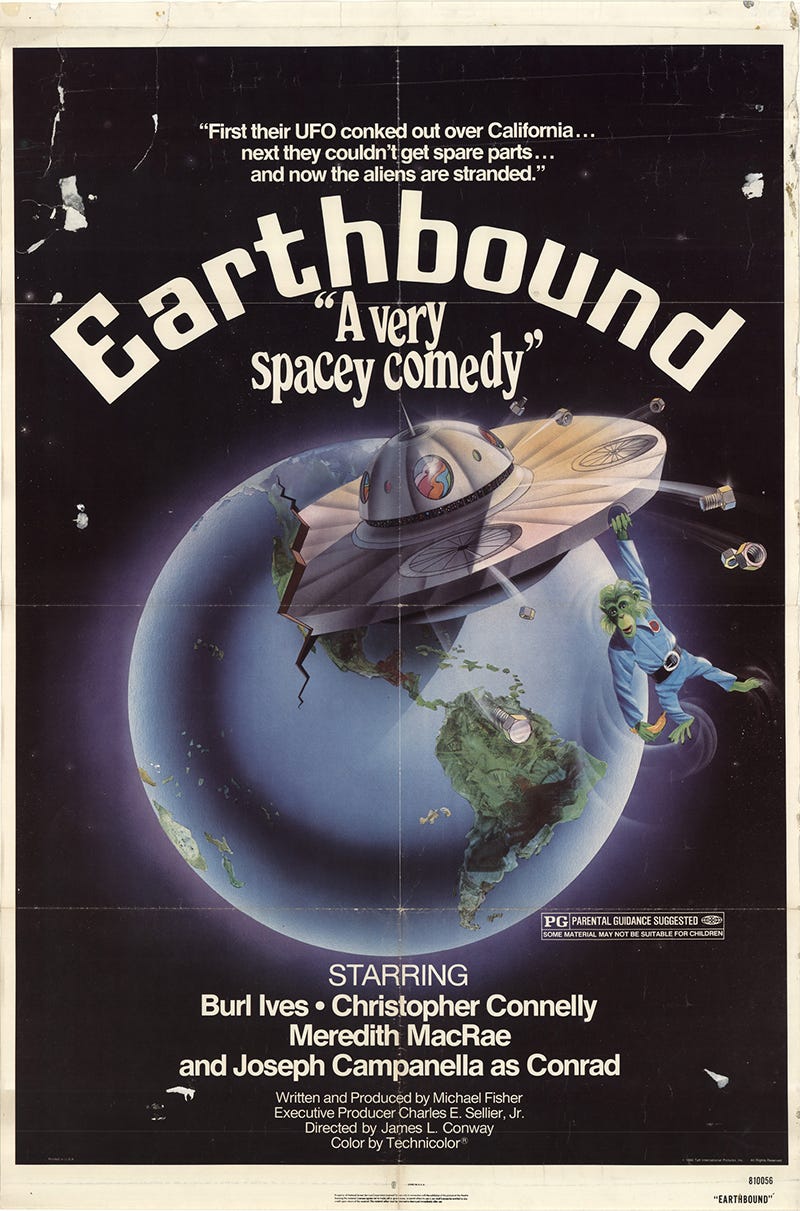

Earthbound

Burl Ives, Christopher Connelly, Meredith MacRae, Joseph Campanella, Marc Gilpin, Todd Porter, Mindy Dow, Elissa Leeds, Peter Isacksen, John Schuck, Joey Forman, Stuart Pankin, H.M. Wynant, Jesse Bennett, Daryl Bingham, David Chambers, Craig Clyde, Bill Couch, Travis DeCastro, Tim Eisenhart, Cindy Epple, William Bruce Estey, Jerry Fleck, April Gilpin, Mel Hampton, John Hansen, Richard Hoag, Richard Jury, Craig R. Larsen, Gregg R. Larsen, Zane Parker, Kevin Parr, Marc Raymond, H.E.D. Redford, Marcia Dangerfield, Max Robinson, William Rowell, Beverly Rowland, Michael Ruud, Dennis Saylor, Steven Sherman, Tiger Thompson, Doodles Weaver, Michael Witt

cinematography by Paul Hipp

music by Bob Summers

screenplay by Michael Fisher

produced by Michael Fisher

directed by James L. Conway

Rated PG

1 hr 39 mins

An alien family crashes on Earth, and a human family comes to their aid.

Taft Entertainment Company started making some big moves in the early ‘80s. A media conglomerate that started in radio, they expanded into both print and television during the ‘50s and ‘60s, also buying the Hanna-Barbera cartoon studio as well. The ‘70s saw an expansion into theme parks, and as the ‘80s began, they made their move into movies by purchasing Sunn Classic Pictures and Ruby-Spears Productions. They were hungry for content those first few years, releasing things they picked up in their various acquisitions, movies like Hangar 18 and The Boogens.

I mention those because they were both directed by James L. Conway, who was apparently working like he was being chased by a bear at this point. He got his start with Sunn Classic Pictures, and he cranked out a few of their early hits like In Search of Noah’s Ark and The Lincoln Conspiracy. He directed a television pilot that they couldn’t sell, and when Taft purchased the company, they reworked the pilot into this feature film.

Let’s just say there’s a reason we did not enjoy 15 seasons of delightful adventures involving the Anderson family and their wacky space monkey. Burl Ives stars as the jovial head of a family who decide to help a family of aliens of who find themselves stranded on Earth. There are goofy local cops and a mysterious shadowy government agent, and the aliens all have super low-budget magical powers that are used for the lowest of low stakes hijinks. Conway has had a long career in television, and he’s done genuinely good work over the years, but at this point, he was still learning on the job and this one feels like it never should have been taken off of the shelf where it was lingering in the first place.

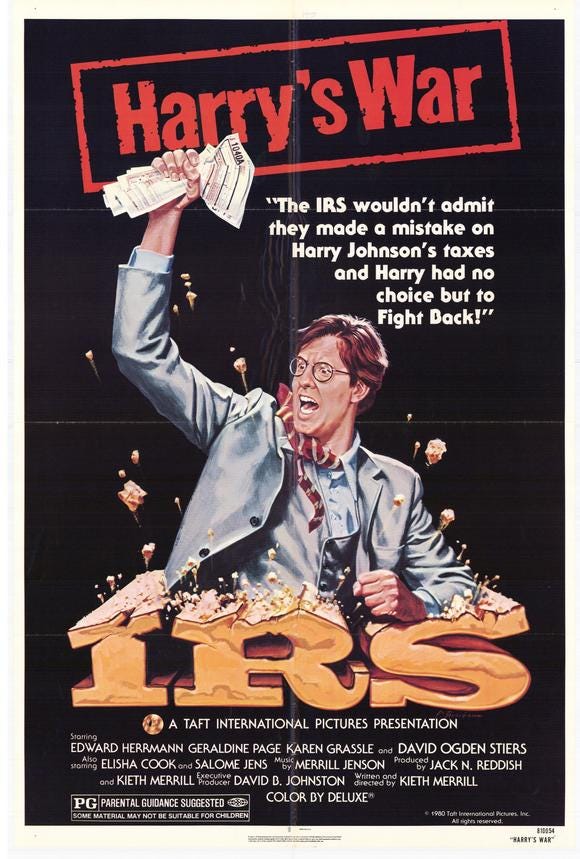

Harry’s War

Edward Herrmann, Geraldine Page, Karen Grassle, David Ogden Stiers, Salome Jens, Elisha Cook Jr., James Rya, Douglas Dirkson, Jerrold Ziman, James MacKrell, Noble Willingham, Prentiss Rowe, Vernon Weddle, Max Lewin, Alan Cherry, Bruce Robinson, Rex Cutter, Kamee Aliessa, Kieri Valee, Scott Wilkinson, David Mason Daniels, Spencer McMullin, Jean Stringham, Leslie Perry, Robert Daugherty, Oscar Rowland, Marc Raymond, David Sterago, Terry Afton Lee, Charles Chagnon, Dolly Big Soldier, Paul Anderson, Larry Roupe, Jack N. Reddish, Leola Green, Star Hermann, Mickey Wodrich, Jay Bernard

cinematography by Reed Smoot

music by Merill B. Jenson

screenplay by Kieth Merrill

produced by Kieth Merrill and Jack N. Reddish

directed by Kieth Merrill

Rated PG

1 hr 38 mins

When an old woman has a heart attack from the stress of her battle with the IRS, the nephew she raised goes to war in her memory.

Taft International Pictures must have figured that quantity over quality was the way to make their mark on the early ‘80s landscape. On the same day they dumped the failed pilot Earthbound to theaters, they also opened Harry’s War in many of the same markets. That would have been a very weird double feature, although both films were made in Utah and ostensibly aimed at the family market.

We just talked about Windwalker, the previous film from director Kieth Merrill, and that feels like it’s a wildly different thing than Harry’s War, both in tone and execution. Harry’s War is about a Capra-esque normal guy, a postman, who gets a distressed letter from the aunt who raised him, and when he brings his family to meet her, he finds that she’s locked in a war with the IRS. She dies whit the issue unresolved, and Harry turns into a crusader on her behalf. There’s a broad wacky sensibility here, and Edward Herrmann seems like a pretty natural fit for the material. David Ogden Stiers is equally well-pitched as the head of the IRS office who is determined to crush Harry, especially once he starts using the TV media to win the public over to his cause.

I would imagine there is a corner of the Internet that looks at this film as sacred text, and it feels like Merrill pulled from the rhetoric of some fringe groups when building Harry’s anti-IRS arguments. Seems like poking a bear in film form, and I’d love to know how many times Merrill was audited after this. Geraldine Page appears as Aunt Beverly, riding herd over a house full of eccentrics, and she’s giving it everything she’s got. This isn’t a terrible film, but it takes the little guy against the system template and then makes some hog-wild choices about how to use the IRS as the bad guy.

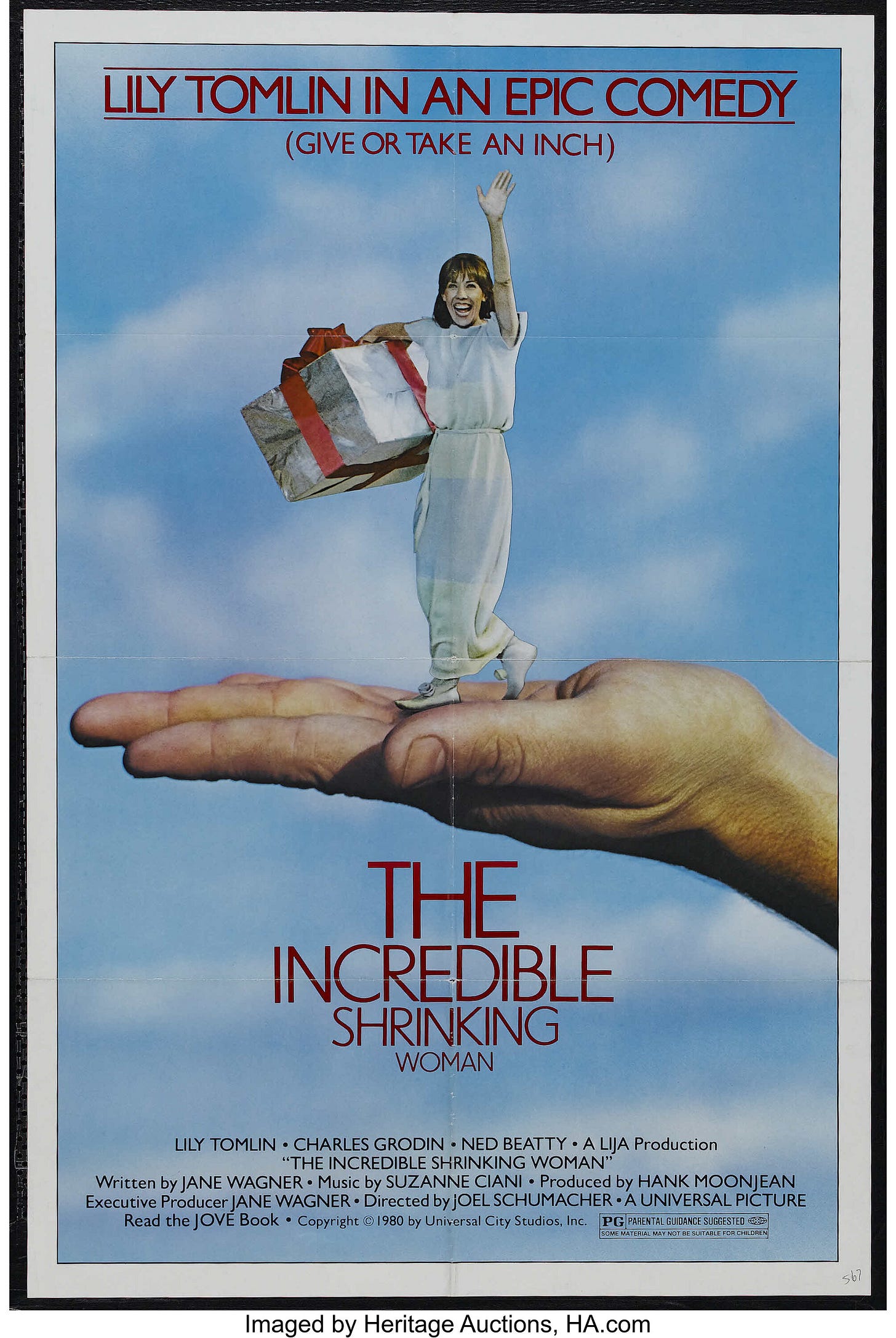

The Incredible Shrinking Woman

Lily Tomlin, Charles Grodin, Ned Beatty, Henry Gibson, Elizabeth Wilson, Mark Blankfield, Maria Smith, Pamela Bellwood, John Glover, Nicholas Hormann, Jim McMullan, Shelby Balik, Justin Dana, Rick Baker, Mike Douglas, Karen Knapp, David Marsh, Mary McCusker, Betty McGuire, Maria I’Brien, Julie Payne, Randy Powell, David Ruprecht, Donovan Scott, Charles Woolf, John Achorn, Martin Ferrero, Ronald E. House, Will Knox, Mitch Kreindel, Nancy Lenehan, Holly McCarver, Mimi Seaton, Alan Shearman, Joe Spano, Ron Vernan, Diz White, Grace Woodard, Jacki King, Macon McCalman, Dick Wilson, Sally Kirkland, Pat Ast, Dorothy Andrews, June Sanders, Jonathan Prince, Terence McGovern, Betty Beaird, Irene DeBari, Dante D’Andre, Todd Everett, Joseph Hardin, Gary Goetzman, M.E. Loree, Robert Phelps, Glenn Robards, James Beach, Dick McGarvin, Julie Brown, Janice Carroll, Annie Knight, Kevin Brando, Randy Morton, Ari Zeltzer, Mitzi Hoag, Albert Marotta, Tom McLoughlin, Jan Stuart Schwartz, Richmond Shepard, Mitchel Evans

cinematography by Bruce Logan

music by Suzanne Ciani

screenplay by Jane Wagner

based on the novel by Richard Matheson

produced by Hank Moonjean

directed by Joel Schumacher

Rated PG

1 hr 28 mins

A housewife begins to shrink thanks to a constant exposure to the toxic chemicals that are part of her daily life.

1957’s The Incredible Shrinking Man is a genuinely great work of visual imagination, with a fantastic script by Richard Matheson and Richard Alan Simmons, based on Matheson’s novel. It’s a haunting film that effectively taps into the existential terror of gradually losing your space in the world. It seems like the last thing you’d choose to remake as your next film if you’re coming off the internationally successful comedy juggernaut that was National Lampoon’s Animal House, but that’s exactly what John Landis chose to do in 1979.

The project was already in development before he became involved. Jane Wagner and Lily Tomlin had been building a creative collaboration on stage and television and in film, and Wagner certainly seemed to understand Tomlin innately. They seemed to share one creative brain between them, and for the most part, what they created was successful and acclaimed. Then Wagner directed Moment By Moment, starring Tomlin and John Travolta, and the two of them hit their first real brick wall as a team. That film was a bomb and pretty much ended any chance that Wagner might be the one to direct her own screenplay for Shrinking Woman. Landis would make sense on one level for Universal. After all, Animal House was a sensation, and it felt like a comedy that spoke directly to an audience the studio didn’t totally understand. They knew they wanted to work with Landis and he had an appetite for old genre movies, as evidenced by the screenplay he kept trying to convince them to make, An American Werewolf in London. Landis brought Rick Baker onboard, and they developed a few drafts of the script with Landis as director, building sets, designing the effects, storyboarding pretty much everything. Even as the budget swelled, Universal kept thinking that they would have to back Landis on his vision right up until the film actually started shooting.

A few days later, it was all over. It took six months before production started again, this time with Joel Schumacher making his directorial debut, the script having gone through a couple of fairly severe rewrites to try to make it affordable. The truth is, looking at the various drafts of the script, the story Landis was going to tell is the same story that Schumacher told. All that changed was the scale of the thing, and even so, it doesn’t feel like they lost any of what was key to the take that Wagner developed. My problem is not that Schumacher is very new to the job and not really up to the task of putting everything together technically while also telling a story that has a strong satiric point of view while also telling a genuine human story. That would be a tonal balancing act that would task any director, and Schumacher walked into an unwinnable situation here.

My big problem is the script. I don’t think it’s funny. Not even accidentally. The film is about Pat Kramer, a normal housewife who is constantly exposed to different chemicals all day long in the kitchen and while cleaning and in her car and at the store and one day, she’s exposed to one thing too many in just the right amount and she starts shrinking. The film’s most obvious satiric point is the way consumerism reduces us all, making us unimportant as people. We are simply data to be sold, consumers to be sold to. That’s a totally valid satirical target, but I don’t think any of the characters Tomlin plays here land. Pat’s a zero, a blank slate at the center of the film. Her nosy neighbor Judith is annoying but not particularly funny. She pops up as Ernestine the telephone operator, and if you don’t give a shit that she played the character on TV, it means absolutely nothing, and it certainly isn’t a laugh of any kind in this context.

Pat’s married to an advertising executive named Vance, played by Charles Grodin in a role that he could have done in his sleep. Grodin’s an amazing comic talent and it bugs me when he’s just hired to skate along in low-grade weasel mode without anything noteworthy to do. Vance works for the more aggressively weaselly Dan, played by Ned Beatty as the exact Venn diagram center between his work in Network and Superman, and the multiconglomerate they work for is eventually revealed, in the form of John Glover, as the film’s ultimate villain. They want to study Pat so they can figure out what made her small so they can shrink the entire population, a very weird plan, but this is all pretty cookie-cutter. Wagner’s strength as a writer does not appear to be plotting, and it’s a real shame they dumped all of this junk into a structure that already worked so well.

Even if they’d stuck closer to Matheson’s original story, they could have still found plenty of room for satire and great character set-ups for Tomlin. Instead, this thing is just shrill and noisy and aggressively ugly. Cinematographer Bruce Logan shot a number of low-budget exploitation films, then graduated to studio fare with I Never Promised You A Rose Garden. After that, he shot this film and then TRON and then basically never shot a studio movie again, which is wild. This film is so garish it’s like getting a continuous thumb in the eye, while TRON feels genuinely adventurous, like he was creating something new. I’m sorry this is one of his biggest films because I suspect he shot exactly what Schumacher asked him to shoot. This is meant to feel like we’re trapped in this ugly plastic hell. I think the film feels very much of its moment, with some insidiously racist stuff about their housekeeper Consuela, while it feels like the way they shoot the stuff with the kids is directly influenced by the way Spielberg and Demme were shooting the chaos of family life at the time.

I do think Schumacher shows promise here, even if I don’t like the movie. There are clever touches, like the casting of Dick Wilson as the local grocery store manager. Wilson was iconic at the time as Mr. Whipple, and it underlines how artificial Pat’s entire environment is even before she’s so small she can live in a literal Barbie Dream House. Rick Baker plays a gorilla in the film, in a suit he designed, and gorillas are a big part of Baker’s upbringing. One of his primary mentors was Bob Burns, who was a long-time suit guy, having played Tracy the Gorilla in the Larry Storch/Forrest Tucker The Ghost Busters. Bob played gorillas for decades, and there was something special about the guys who designed their own suits and then played the part. Baker did it for King Kong as well after the much-ballyhooed giant Carlos Rambaldi mechanical Kong didn’t work, and anything that is effective about the performance of that Kong comes down to Baker. His work is Sidney the gorilla in this film is big and broad and silly and largely played with either a tiny Tomlin or Fridays star Mark Blankenfield as the high-strung lab assistant who helps Pat escape, and it’s the stuff that people talk about when they remember this fondly as a film they saw as children.

Ultimately, the blame for the film’s creative failure has to fall at the feet of Lily Tomlin. This was one of the few films where she was calling pretty much every shot. Her wife and partner, Jane Wagner, is obviously a huge part of her creative process, but this material didn’t fit Wagner’s sensibilities at all. It’s wild that Tomlin tried to quit 9 to 5 several times, even after it was already filming, because she was so worried that the film would damage her comic credibility. Reportedly, it was the Snow White fantasy sequence that she saw as a breaking point and they really had to convince her to stay and finish shooting. Watching pretty much any set piece in this film, I have trouble imagining what made her think this was smarter or more adult or more comedically worthwhile than 9 to 5. This did real damage to her ability to get a film made, and it pretty much derailed her until Carl Reiner took a chance on her in 1984’s All Of Me. I wish we’d seen a complete comedy original from Tomlin and Wagner instead of this oddball reworking of such smart and serious source material. In the end, I can’t imagine anyone involved walked away feeling like they’d done what they set out to do, and I can only recommend it as an example of how the best intentions can result in something truly heinous.

I PULLED A BONER

If you’re familiar with ‘80s All Over, then you know what this means.

As meticulous as I am about trying to get the research right on this, there are going to be mistakes made along the way, and it just seems inevitable. Everyone pulls a boner sometimes. Sometimes it’s a big boner. Sometimes it’s a small boner. You may not mean to pull the boner, but no matter… that boner gets pulled.

We’ve just wrapped up 1980, and as I get started on 1981, I’ve come up with about five titles that should have appeared over the course of the last 12 months. I’ve been thinking about how to handle it, and I think I have the answer.

You’ll get a special issue of this newsletter sometime in August. You’ll see the Joker right there at the top, and in it, you’ll find those five reviews. Then I will place those reviews into the archived version of each newsletter where they originally should have appeared so if you go looking at, say, December of 1980, the archived version will be fully updated and correct even though the one that originally appeared in your email inbox wasn’t.

I welcome any and all corrections you guys send because it means that the final archival version of this project will be as accurate as possible.

AND FINALLY…

January 1981 was a solid episode for us on ‘80s All Over, and I think the same thing happened to us at that point that happened to me after I published last month’s newsletter. There’s a feeling you get after you complete a major piece of a project like this. You start to feel like it’s actually possible.

I know we’ve got a long way to go before I get to put this project to bed completely, but it is going to happen. It is an actual possible thing. And so are the books that will collect each year of this project. I’m currently starting work on the process of turning the first year of this project into a finished book, something worth keeping on your shelf, expanding and editing the reviews that were published here and adding a few more essays about the year. It will not be a quick process, and I suspect I’ll be at least two or three years deep in the newsletter before the first book actually sees print.

As always, your support is what keeps this train moving. Thanks for subscribing, and if you are reading this and you haven’t already subscribed, please do! It’s just $5 a month, and it’s less if you buy a whole year at once. And if you’re already subscribed, then why not give someone a gift?

I’ll be back on August 15th with the kickoff of our next month’s coverage. And what should you expect next month? Well, we’ve got a disastrously racist star vehicle, Paul Newman in a not-quite-typical cop movie, Charles Bronson in a Peruvian ripoff of Casablanca, a couple of better-than-average slasher movies, Ralph Bakshi’s most epic movie, and a fistful of foreign titles, including some early crazy Paul Verhoven. Sounds great, right? Wellllllllllll…

Slight correction: that Resnais film is "Last Year At Marienbad."