August 1981 features the ultimate animated cult classic, an American Werewolf, Kathleen Turner's explosive debut and a great Sidney Lumet epic

Plus one seriously odd live-action Disney film

The premise is simple, but the task is not. Every single movie released in the United States during the 1980s, reviewed in chronological order, published month by month.

Buckle up, because this is The Last ‘80s Newsletter You’ll Ever Need…

AUGUST

“Video Killed The Radio Star” when MTV went live at 12:01 AM on August 1st.

13,000 Air Traffic Controllers walked out, and Ronald Reagan threatened to fire them if they didn’t get back to work immediately. Three days later, that’s exactly what he did.

The Waltons said good-bye to John-Boy for the last time.

And in court, John Hinkley begged for mercy and pled innocent to shooting Ronald Reagan, while Mark David Chapman was sentenced to 20 years to life for killing John Lennon.

The arrival of MTV is not the same as the moment when MTV became a real cultural force, but from the second it went live, it was a source of great contention in my home. My parents were, like many parents of the ‘70s and ‘80s, a strange mix of permissiveness and restrictiveness, and often for reasons they could not articulate to me at the time. One of the recurring themes of this stretch of early adolescence for me was the frustration caused by the differences in what I wanted to watch and what my parents were comfortable with me seeing, and this month was distinguished by how many times I was met with an emphatic no from them.

My trips to the mall at this point all followed a familiar shape. My mom or my dad or both of them would tell me we were going to the mall. When we got there, we would set a time to meet, and then I was on my own. I would hit the B. Dalton Booksellers and then the Peaches records and, if I was feeling particularly saucy, I’d throw in a trip to Spencer’s Gifts. Depending on how long we were going to be there, I might go to the theater and the food court at some point, but for anything R-rated, my parents had to be involved.

One afternoon, I saw a record at Peaches that I decided I had to have. The cover art, the line-up of bands on the back, and my already intense fascination with the magazine all made Heavy Metal a no-brainer for me. I bought the double-album and I took it with me when I went to the bookstore. I picked up the August 1981 issue of Heavy Metal magazine, which had a giant layout about the movie. I found myself trying to imagine what something like “Veteran of the Psychic War” might sound like. I was very excited about all of it…

… until I met my mom to go home and she asked me what I bought. I showed her the cover of the magazine, and that didn’t seem to be a problem. The album, though? Something about the Richard Corben artwork on the cover or the term “heavy metal” or the overall vibe of the thing just set her off and she told me I had to take it back. She made me go to Peaches and return the album, and the more I asked her for a reason, the less interested she was in explaining herself. She just plain bounced off everything about that soundtrack album and she told me there was no way I was going to go see that movie.

That is why god created good friends and older brothers, though. The rule was “parent or guardian,” and my friend’s two older brothers were more than happy to play that part, especially if they thought a movie was going to be particularly fucked up. The mere idea of an animated film filled with nudity and violence was enough to get them onboard, and so I had a sleepover at my friend’s house and saw the film with them and absolutely lost my mind for it. I still wasn’t able to bring the soundtrack home, though, until a few years later, after it fell off my mom’s radar. The vehemence of her reaction on that first day made this movie an absolute must-see, something I’ve tried to remember now that I’m a parent. I had to see why she was so upset about this thing, and to be fair, it felt wildly transgressive for an eleven-year-old.

My dad introduced me to one of his favorite up-and-coming movie stars this month when we went to an afternoon showing of An Eye For An Eye. I never quite understood the appeal of Chuck Norris, even if I enjoyed going to see his movies with my dad. I always thought Norris was a lug, a galoot, a big block of wood. My dad was a judo enthusiast and really loved watching pretty much any kind of martial-arts action film, and Norris was an instant star as far as he was concerned. Years later, I was a judge at a film festival that was started by Chuck Norris and his brother Aaron, and as part of the festival, I had a Sunday morning hangout with Norris and the other judges. The festival took place in the town where my parents have retired, and happened to be directly across the street from their house, so I took no small pleasure in introducing my father to Chuck Norris and leaving them to a conversation for a few minutes, bringing everything full circle.

I was rewatching the summer’s biggest films repeatedly at this point. I took every opportunity to go see Raiders of the Lost Ark over and over and over, and anyone who I heard was going was a potential ride for me. Same thing with Superman II or Escape From New York. I managed to see Stripes more than once as well. Movies had a habit of lingering in theaters for a much longer time if they were popular, and there were so many more opportunities to see something over and over. Even though I had a VCR in my house by this point, I knew that movies would disappear for a long time after they were in theaters and that there was something different and special about seeing them with audiences. I was learning to watch the audience as much as the movie as a way of trying to decipher the magic trick when something really landed on me like a ton of bricks.

There was no greater magic trick in August of 1981 than Rick Baker’s incredible work in the John Landis horror/comedy An American Werewolf in London, and this may have been the moment that my growing interest in movie effects make-up erupted into a full-blown obsession. As I’ve mentioned here before, Fangoria was the source of great turmoil in my house. I loved the magazine and my father loathed it. I saw it as a guide to explaining the upsetting magic tricks in these movies, while he saw it as a celebration of the profane. Rob Bottin’s werewolf work in The Howling was remarkable and that movie was so mean and rough that it felt dangerous to me. Knowing that the guy behind Animal House and The Blues Brothers was making this werewolf film definitely made it seem like the more user-friendly of the two before seeing it, and knowing that Rick Baker was the guy in charge of the transformation, which seemed to be the main selling point of the film, had me determined to see it no matter what. I knew my parents would never take me, so I didn’t even try to talk them into it. The older brothers we usually turned to announced that it was “too much” for us and they couldn’t be responsible for exposing us to something so ruinously terrifying. This only made us more determined to get in to see it, though, and we finally talked an older sister into it. She thought David Naughton was cute on the poster and that was enough to get her to take four of us to see it on a Saturday afternoon. She probably regretted that around the time she found herself surrounded by pre-pubescent boys during a prolonged sequence set in a porno theater, but she was a hero for putting up with it. The film absolutely blew my mind and I needed to know how everything in the film was accomplished. I thought Griffin Dunne was the funniest dude on the planet, I formed the most painfully dire crush on Jenny Agutter imaginable, and I went completely mad for the make-up effects in every scene. I was finally able to convince my mom to see the film when it came out on home video, where I had to study it over and over to figure out how Landis made everything work so well together, this crazy blend of comedy and horror.

The battle over Body Heat did not end as well. As I’ve said, I was Raiders of the Lost Ark crazy this summer, so hearing that the writer was making his directorial debut with a movie that was a throwback to old Hollywood thrillers had me agitating to see Lawrence Kasdan’s Body Heat in theaters. Nope. My parents saw the film together and made it clear that they were not interested in me seeing it, and no one my age was particularly interested in going. It was a reminder that while I was regularly consuming adult-oriented content already, my options for doing so were limited and I often found myself frustrated. Home video was becoming the battleground where I could win every fight given a long enough runway, but R-rated films in theaters remained a special occasion that required strategy from me if I wanted to make them happen.

We’ll kick things off today with a movie my parents happily took me to even though I was pretty sure I didn’t want to see it. I was starting to dread Disney live-action comedies, and this first film did nothing to convince me I was wrong…

AUGUST 7

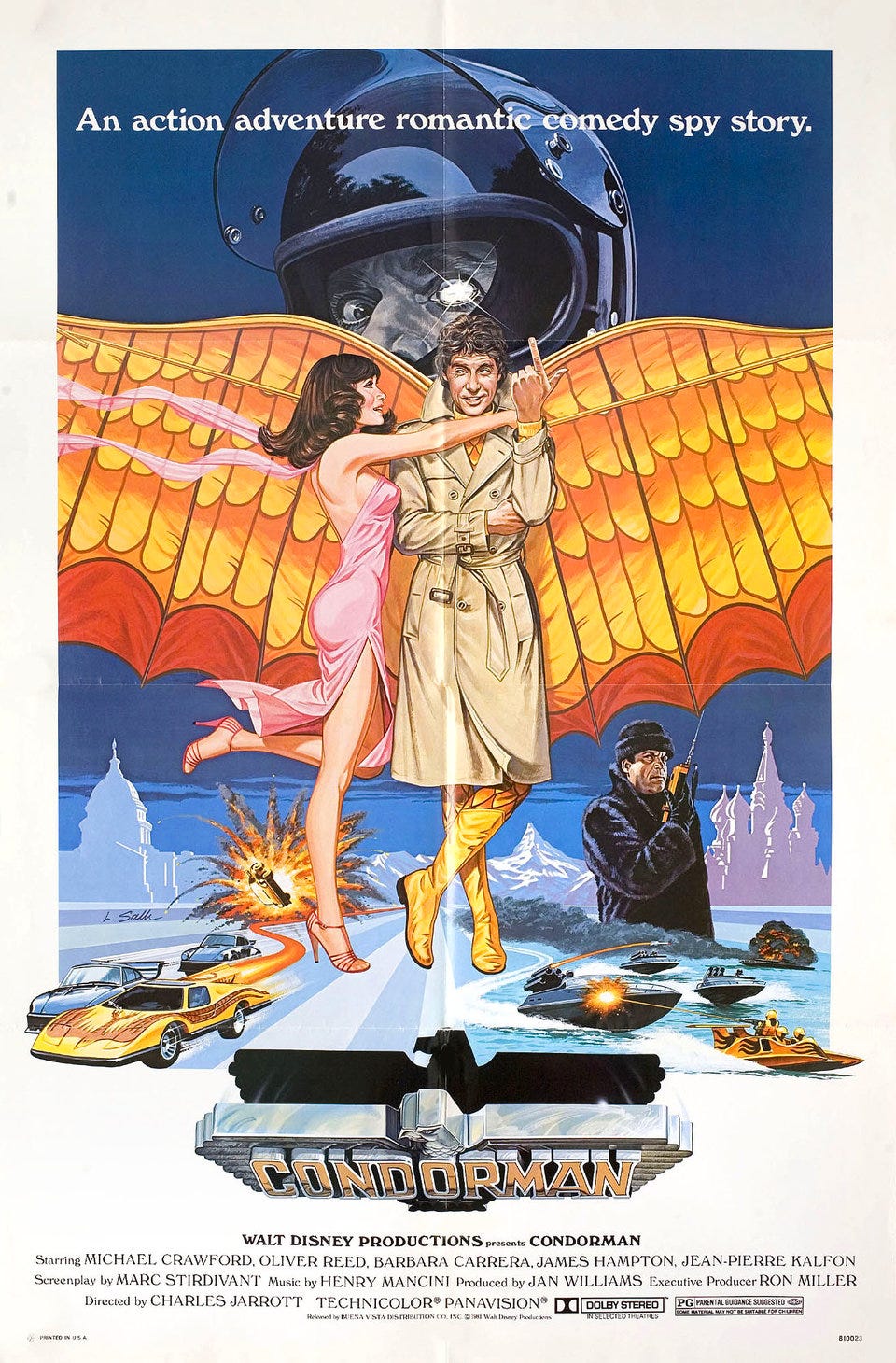

Condorman

Michael Crawford, Oliver Reed, Barbara Carrera, James Hampton, Jean-Pierre Kalfon, Dana Elcar, Vernon Dobtcheff, Robert Arden

cinematography by Charles F. Wheeler

music by Henry Mancini

screenplay by Marc Stirdivant

based on the novel The Game of X by Robert Sheckley

produced by Jan Williams

directed by Charles Jarrott

Rated PG

1 hr 30 mins

A cartoonist is given a chance to live out his dreams of being a spy and finds himself in over his head.

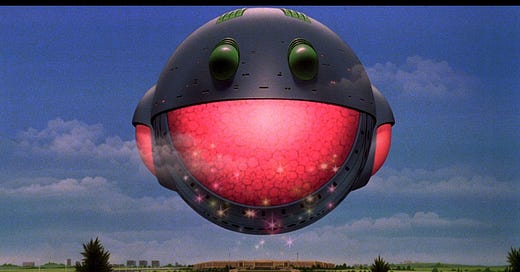

The closest Disney’s come to reclaiming this film was in a Pixar short called “Small Fry,” and in this clip, you’ll spot Condorman in the Discarded Toys Support Group, sitting in his Condor Car. I’m guessing very few people got the joke because this film was a total whiff when it was released originally. It has its fans, certainly. A friend of mine is unyielding in his love for the movie, and I like certain things about it, but it suffers from the same major tonal issues that most of the Disney films of this era ran into.

There’s an idea here (a cartoonist who gets involved in a mission just like the superhero he draws/writes) that is a lot of fun, and which has very little to do with the Robert Sheckley novel it was based on in the first place. That book, written and published in the mid-‘60s, is a send-up of the spy genre, telling the story of a low-level courier on a spy mission who is mistaken for a much more important spy than he actually is. The film was purchased by the studio during the early days of Ron Miller’s run as President and screenwriters Mickey Rose and Marc Stirdivant were put on the project. They were the ones, perhaps inspired in part by 1965’s Jack Lemmon vehicle How To Murder Your Wife, who came up with the idea of making the character (named Bill Nye in the novel) a cartoonist who gets caught up in real-life spy games when he’s pretending to be his own main character. The Lemmon character and Woody Wilkins (Michael Crawford) both have someone else photograph them in costume so they can use those photos as reference for their art, but in Condorman, that leads to Woody becoming involved in a CIA plot to rescue a potential defector from the KGB. Rose was a comedy writer who worked on variety shows and sitcoms as well as the early Woody Allen films Take the Money and Run and Bananas. He left Condorman to go focus on his own film, which oddly enough ended up coming out the same day, and we’ll discuss that one below. Meanwhile, Stirdivant stayed on the film and ended up working in the Disney system for a while as a result.

By this point in his career, director Charles Jarrott was settling into his role as a “traffic manager,” as Pauline Kael once described him. His early costume drama work is fairly stiff and formal, and his later work is marked by a near-total lack of style. We’ve already discussed one of his live-action Disney films, the labored The Last Flight of Noah’s Ark, which was a decided left-turn for him as a filmmaker. Not a particularly successful one, either. I have no idea why he was their choice for that film or for this one, and he doesn’t seem to have much of a flair for action or comedy, the two things that the film ostensibly needs to succeed. It’s clear that they wanted this to be a Pink Panther-like franchise of films, complete with an animated opening title sequence and a ton of wacky slapstick, and hiring Henry Mancini to write the score felt like they were calling their shot.

Maybe the biggest misstep for me is the casting of Michael Crawford. This was released right around the time Crawford began his legendary run on Broadway in Barnum, and obviously he created another iconic role when he appeared onstage in The Phantom of the Opera. Crawford is a talented guy who can blast it to the back row of the theater in a live setting, but that doesn’t necessarily translate to film. He’s playing this big and broad and on a whole different wavelength than, say, Oliver Reed, who looks like he wants to eat Crawford’s face in every scene they have together. The best way to view the film is like a gateway drug to James Bond films, intentionally pitched at children as a way of teaching them some of the tropes that the more adult films lean on. There are car chases, explosions, laser weapons, boat stunts, and flying people, and that all sounds incredibly exciting. I even walked into this one pre-sold on it because Disney serialized the entire film into Sunday newspaper comic strip form starting in December of 1980 and running through April of 1981. I remember reading the entire thing and enjoying it well enough. The film doesn’t work for me from the very beginning, though, and I would imagine it plays even worse now to a generation of kids who have grown up with good superhero movies a-plenty. There was a time when we had to settle for offerings like Condorman, but it feels at this point like a relic of a moment when this studio truly had no idea what they were doing.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Last '80s Newsletter (You'll Ever Need) to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.